How The Dutch Rigged The Outcome Of The MH17 Trial (On A Charge That Requires No Proof) Tyler Durden Fri, 06/26/2020 - 03:30

Authored by John Helmer via Dances With Breas blog,

The Dutch Government has devised an evidence-proof scheme for ensuring the trial of the Russian government for the destruction of Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17 will end in a conviction.

This scheme will work without evidence to prove that the four men accused of the crime of shooting down the aircraft, killing the 298 passengers and crew on board on July 17, 2014, intended to kill; or even intended to fire the missile which allegedly brought MH17 down.

The Dutch scheme is evidence-proof because no evidence will be needed, not from US satellite photographs which are missing; nor NATO airborne tracking which shows no missile; nor Ukrainian Security Service (SBU) evidence which has proved to have been fabricated, and in the case of Ukrainian witnesses for the prosecution, threatened, tortured or bribed.

The scheme is also evidence-proof because the Dutch Prime Minister has told the Dutch Minister of Justice to order the state prosecutors to tell the state-appointed judge that he must convict the Russians if he finds as proven that MH17 crashed to the ground in eastern Ukraine; that everyone on board was killed; and that the four soldiers accused – three Russians and one Ukrainian – were on the ground fighting.

International war crimes lawyers are calling this a legal travesty. It was presented in court near Amsterdam by Dutch state prosecutor Thijs Berger on June 10. It has gone unnoticed in the mainstream western media. Russian reporters following the trial have missed it. The scheme was first reported in English and Russian by a NATO propaganda unit on June 12.

As a prosecutor of the Dutch War Crimes Unit, a state entity, Berger has been employed in the past to prosecute the targets of wars fought by the Dutch, alongside NATO and the US, in Yugoslavia and Afghanistan. In Europe his group prosecuted war crimes alleged by the NATO alliance in its war on Serbia from March to June of 1999. A recent report [2]to which Berger contributed, entitled Universal Jurisdiction Annual Review 2019, identifies a case which Berger pursued of war crimes in Afghanistan; those alleged crimes were not of the US and allied forces in Afghanistan, but of the local Afghans defending themselves.

Prosecutor Thijs Berger announces the evidence-proof scheme of Article 168. The legal loophole is spelled out over six minutes – Min 3:31:00 to 3:37:00.

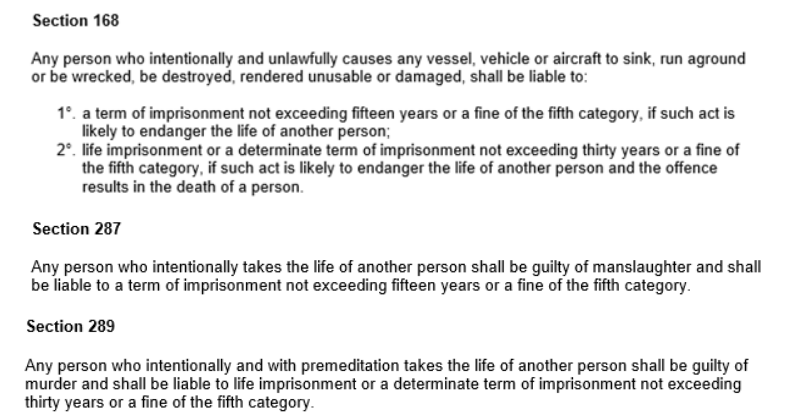

For his presentation to presiding judge Hendrik Steenhuis, Berger read from a multi-page script authorized by his superiors in the Dutch Ministry of Justice and Security. They and he repeatedly made the mistake of calling the charges in the prosecution’s indictment – Articles 168, 287 and 298 – provisions of the Dutch Code of Criminal Procedure. This is the procedure code; its provisions are called articles in the original Dutch, but sections in the English version.

The charges of the indictment are from the Dutch Criminal Code. They are called articles in court; they are called articles in the Dutch statute but sections in the official English translation.

Source: The Dutch Criminal Code

For analysis of how the prosecution has manipulated both the Criminal Code and the Code of Criminal Procedure in the MH17 trial preliminaries, read this.

“The scope of the indictment,” Berger began his legal argument, is that together, the four defendants — Igor Girkin (Strelkov), Sergei Dubinsky, Oleg Pulatov, who are Russians, and Leonid Kharchenko, a Ukrainian – played “a steering, organizing, and supporting role in deploying the BUK-Telar [missile and radar unit]” to shoot down MH 17 (Min 3:25:22). They were members of an “armed group” engaged in “armed struggle, the purpose being to shoot down an aircraft” (Min 3:27:20-21).

Note the indefinite article – an aircraft. The prosecution is charging the four with capital crimes for defending themselves from attack by the Ukrainian Air Force. This, however, is not mentioned by the prosecution.

“They are not being prosecuted,” Berger went on, “as the persons who actually carried out the firing process” (Min 3:38:22). “We do not need evidence as to the exact cause of events in order to be able to judge the accused” (Min 3:28:27). Homicide or murder, Berger conceded, is in Dutch law “death caused intentionally” (Min 3:29:15). But the crimes which must be judged by Steenhuis and his panel of The Hague District Court, he claims aren’t homicide in the usual legal sense. “The exact course of events need not be established” (Min 3:30:43), Berger told Steenhuis. So the prosecution does not need to prove what happened. “That the missile which hit the MH17 could possibly have been meant and intended for a military aircraft doesn’t change these facts” (Min 3:31:17).

“None of the charges in the indictment requires intention concerning the civilian nature of the aircraft or the occupants. The crimes in the indictment forbid the downing of any aircraft; this is Article 168 of the Code of Criminal Procedure [sic]; and also forbid causing the deaths of others under Articles 287 and 289 irrespective of whether the aircraft has a military or civilian status, and an error in the target doesn’t really make a difference for the evidence that these crimes have been committed. So no evidence is required that the accused should have had the intention to shoot down a civilian aircraft” (Min 3:32:00).

“It was their intention to down a military aircraft of the Ukrainian Air Force” (Min 3:32:28), Berger claims his evidence of the SBU telephone tapes and witnesses proves.

“Those who intend to shoot down a military aircraft and subsequently, accidentally, hit a civilian aircraft are guilty of causing an aircraft to crash according to Article 168 of the Code of Criminal Procedure [sic]; but also guilty of murder of the occupants according to Article 289 of the Code of Criminal Procedure [sic]” (Min 3:33:04).

In a regular court of law in England, Australia, Canada or the US, a prosecutor’s legal argument is always presented with explicit references to the case law. That’s the accumulation of judgements by courts going back as far as the history of the crime and of the statute can be traced. These are the precedents which, in international law and in Dutch law too, must be followed by judges hearing cases to which these precedents apply. This reflects the accepted notion that law is cumulative, and that judges administer and interpret that law; they don’t issue personal opinions or preferences.

Berger didn’t identify any Dutch case law or provide the court with precedents in previous cases decided by the Dutch courts.

The reason is that there are none , explains a veteran Dutch judge who was asked this week to identify the case law on Article 168. The judge replied: “It’s sufficient to establish that the defendant had the intention to take down some aircraft and that he should have seriously taken into consideration the chance that he would hit an aircraft such as the MH-17. That’s called conditional intent — voorwaardelijk opzet in Dutch… Answering this question [of precedents] took a bit more time. I couldn’t find any case law that would be relevant to the issue. Article 168 is not used very often.”

Conditional intent doesn’t exist in Anglo-American law. But in Dutch law, the concept has not (repeat never) been applied to cases of warfare, or in situations of military engagement where men are attacking and defending themselves. For a Dutch review of the court precedents for application of voorwaardelijk opzet to deaths caused by a drunk driver and a poisoning, read this [8]– Sect. 3.3.1. Fatal traffic offences committed by drunken drivers are the typical homicides in which Dutch prosecutors apply the doctrine of conditional intent; the case law and precedents are reviewed here [9]. No Dutch lawyer, judge or court has ever applied this to warfare.

Berger knows this; so does Steenhuis. They also know there is voluminous case law in the international courts dealing with similar facts to those of the MH17 case and of the combat in which the four defendants were engaged; for a sample Dutch law review, read this.

Again, Berger ignored what no prosecutor outside The Netherlands would attempt in front of a judge. “We are aware,” Berger told Steenhuis, “of academic comments that imply that Article 168 would require intention in killing civilians [Min 3:33:04]. But this is incorrect. Article 168 does not require any intention for the death of the occupants” (Min 3:33:34).

The NATO propaganda unit Bellingcat repeated this claim in a publication two days after Berger’s presentation. The Article 168 argument, repeated from Berger’s script, will prove to be a “boomerang” for the Russian government, NATO officials are now claiming. “It is only a question of time, therefore, that the Dutch prosecution brings murder charges against Russian top military commanders. Unlike the case with the 4 defendants, they would easily have obtained combatant immunity, if only they – and their supreme commander – had admitted to being part of the war. But they – and he – continuously denied, and this alone makes immunity impossible. Also unlike the 4 defendants, the political price that Russia will pay such indictments will be much higher. It is one thing for 3 Russian ‘volunteers’, forgotten by most, to spend the rest of their life holed up at home and afraid to take any trip abroad. It’s an altogether different story when top Mod [Ministry of Defence] and FSB officials – and maybe even a minister – are charged with murder of 298 civilians and end up on the Interpol red-notice list.”

International lawyers already before the European Court of Human Rights are arguing that the “boomerang” strikes the government in Kiev first, because it was ordering combat in eastern Ukraine, including orders for bombing and strafing by the Ukrainian Air Force, and at the same time refusing to close the airspace to civilian aircraft. The case of Denise Kenke, on behalf of her father, MH17 victim Willem Grootscholten, explains.

Canadian war crimes attorney Christopher Black (right) says the Dutch prosecution is deliberately ignoring Dutch law, as well as international law.

“What Berger is stating is a case of criminal negligence, not murder. The general principles of criminal law apply to this case as much as to any case. As for the burden of proof, the court has to be convinced on the basis of the lawful evidence presented that the accused has committed the crime he is accused of.”

Black is pointing out that the prosecution’s evidence from the Ukrainian SBU is unlawful. For analysis of evidence tampering by the SBU, read more .

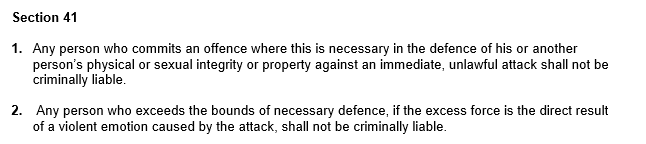

“’Any person who intentionally and unlawfully’— that’s the key phrase in the wording of Article 168. Its use there means specific intent. Specific intent. A general intent to use missiles on something is not good enough in this case. It is telling that [Berger] does not make the distinction between specific intent versus general intent. That indicates the prosecutors don’t think they can prove the necessary specific intent. And if the plane had been shot down by the accused thinking it was engaged in an attack on them or masking [a Ukrainian Air Force] attack on them, then the court cannot convict. That’s because the facts would show an accident or a justifiable act of self-defence.”

In Dutch courts, there are several of what are called “full defences” to indictments for murder. One is insanity; another [14] is duress. Self-defence is the third full defence; it is spelled out in Article 41 of the Criminal Code:

Source: http://www.ejtn.eu/

European lawyers observing the MH17 trial have noted that Berger failed to mention that. They interpret this as an indication the prosecution already believes Judge Steenhuis has decided on conviction.

“The term ‘unlawfully’ is used in Article 168”, Black continues, “because there may be situations where at sea, for example, a vessel has to be grounded or sunk because it is a danger to other shipping or to the crew — or to save the crew. It’s harder to think of a plane that must be crashed for a comparable reason. But one can anticipate the scenario – for example, when men on the ground believe on reasonable grounds that an aircraft was about to bomb them – when attacking the plane would not be considered unlawful because it is self-defence.”

“So the Dutch prosecutors are trying to prove there was an intent [to fire at an aircraft] and therefore they did it, even if there is no evidence they did. I didn’t realise courts dealt in smoking guns. They ought to be dealing in hard evidence. The fact that someone fantasizes about a woman and she ends up getting pregnant and then she has a miscarriage can’t be turned into the accusation against the man of intent to make her pregnant, and then of causing her miscarriage, and so guilty of bodily harm.”

https://ift.tt/2BFpjEc

from ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2BFpjEc

via IFTTT

0 comments

Post a Comment