China Will Be The First Country To Launch A Digital Currency: What Happens Then

By Wim Boonstra of Rabobank

Summary

- China may be the first major country to launch a central bank digital currency or CBDC

- The Chinese CBDC, named DCEP, will strengthen the position of the central bank and help to further modernize the Chinese economy

- The DCEP will probably also be available for China’s trade partners, to begin with Africa

- The DCEP may strengthen the international position of the renminbi to the detriment of the euro

- The arrival of the DCEP should be a strong wake-up call for Western, especially European, policymakers

Introduction

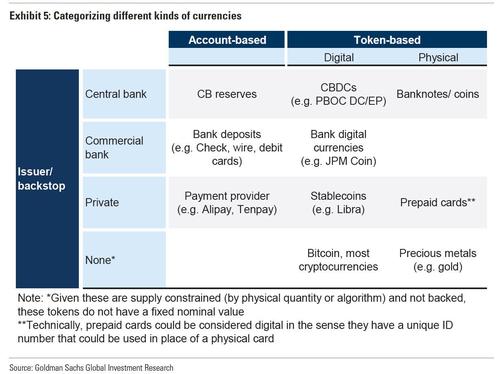

Most central banks are busy preparing for the potential introduction of central bank digital currency (CBDC). CBDC is a digital currency issued by the central bank. It is sometimes referred to as a digital version of a bank note, but in many cases this is not correct. There are indeed many different potential variants.

So far, virtually all the central banks are keeping their options open as to whether a CBDC will ultimately appear.

China, where a far-reaching trial is under way, is the major exception. If this trial is successful, one can expect the Chinese CBDC to be introduced widely in the near future. China is therefore comfortably leading the way because the country has big ambitions for its digital currency. First, it should provide a sizable boost to the Chinese economy; second, it will concurrently further increase the Chinese government’s control of Chinese society; finally, the new currency is part of an ambitious plan to strengthen the international position of the renminbi, the Chinese currency, and potentially at the expense of the euro in particular. This Chinese decisiveness should spur European policymakers into action by further strengthening the euro.

China: from cash-based to almost completely cashless money in 10 years’ time

Not so long ago, retail payments in China were still almost entirely made in cash. There has been a revolution in payments traffic since that time, and China is now one of the leading countries in cashless payments. Unlike in other countries, such as the Netherlands and Sweden, in China this development did not originate from the banking system, but it was induced by a few key apps from relatively young Fintech companies such as WeChat (Tencent) and Alipay (Ant Financial). These parties, that form a kind of extra layer between the banks and their customers, now have a collective market share of more than 90% in Chinese payments cashless retail payments. The Chinese cashless payments system is already able to settle approximately 100,000 transactions per second.

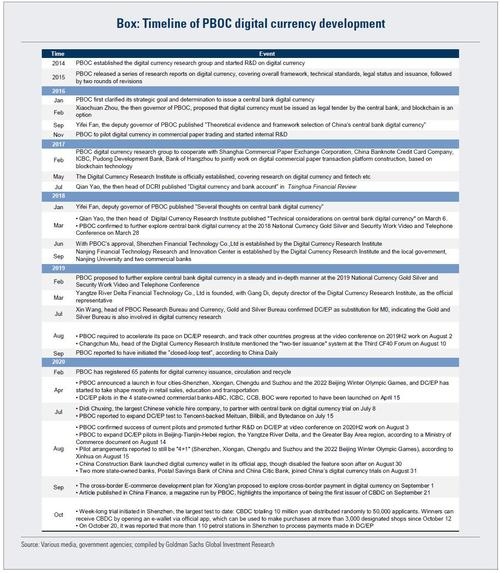

The Chinese CBDC: DCEP

Against this background, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC), the Chinese central bank, has taken the initiative of developing its own digital currency known as the Digital Currency Electronic Payment (DCEP). Above all, the DCEP is a digital alternative to bank notes, although it has features that differ from cash in certain respects (see below). The DCEP does however have the same value as a renminbi.

The technology that can be used by the public for payments is based on traditional payment technology and not on blockchain technology. This is the only way to achieve the necessary scale. The aim is to reach a capacity of 300,000 transactions per second. The central bank might itself use blockchain, for example for wholesale transactions or settlements in DCEP between private banks. Although the DCEP is a cashless currency that will be held in an account with a private entity, there is also the possibility of using a token-based functionality on for example a chip to effect peer-to-peer payments, even where there is no Internet. This is especially needed for successful adoption in the rural areas of China. This token-based functionality will be widely used, as a result of which the DCEP will compete with cash. A sizable trial has been running for several months in which tens of thousands of people have been participating.

What does the PBoC want to achieve with the DCEP?

The PBoC has several objectives with the introduction of the DCEP.

Prevention of a monopoly in the payment system

The PBoC wants to prevent a situation in which WeChat and AliPay take over the Chinese payment system. It is concerned that the entire payment system will soon fall into the hands of these private parties. The DCEP therefore has to restrict the involvement of these parties and increase the role of the central bank in the payment system. It is even more likely that any key private firm will be prevented to become a dominant player, as ultimately China is not a ‘normal’ market economy (which explains Beijing's current crackdown on Ant Financial far better than just a feud between Xi Jinping and Jack Ma).

Promotion of financial inclusion and further reduction of the role played by cash

Highly efficient cashless payments dominate in large parts of China. But in the poorer regions, especially the rural areas, people have less access to banking services such as regular credit. In these areas, cash still plays an important role. Payments in the criminal underworld, including the illegal gambling industry, are also still largely made in cash. The DCEP will offer people in these regions full access to financial services, but it can also reduce the importance of cash payments. The main aim of the DCEP is therefore to replace cash. In terms of features, it will also closely resemble cash.

Better information on payment flows and prevention of illegal transactions

Unlike payment transactions using a bank account, which by definition leave traces in a bank’s records, cash payments are highly anonymous. As we have said, the DCEP will closely resemble cash, with the possibility of making payments directly from one person to another. Some degree of anonymity would thus appear to be safeguarded. But on further consideration, it becomes clear that the PBoC, and therefore the Chinese government, will have full insight.

To be precise, in a transaction between two people effected with DCEP, anonymity between these two people will be assured, as is the case with a cash payment. But the PBoC can always establish at a later date who were involved in the transaction. This will enable more effective tracing of illegal transactions than if these were effected in cash. But there will also be detailed insight into the payment behavior of individuals.

Restricting capital flight

Although China does not have free cross-border capital movements, capital flight is a common and substantial phenomenon. Capital flight can occur in various ways, and is often difficult to trace. For example, internationally trading Chinese companies can for instance manipulate invoices, as a result of which money can be transferred abroad. People can also use the Bitcoin system to hide money from the authorities and/or transfer it abroad.

The Chinese government, like its counterparts in Europe and the US, is concerned that stablecoins could assume an important role as an alternative to the regular money in circulation, but also may develop into a vehicle for capital flight (read "How The Chinese Use Illegal Online Gambling And Tether To Launder Over $1 Trillion Yuan"). Stablecoins are cryptos like Bitcoin, but unlike Bitcoin they are, at least in theory, secured by financial assets. When Facebook announced in April 2020 that it intends to add national stablecoins to its Libra, a digital currency basket that it announced in 2019, central banks reacted immediately by devoting more urgent attention to CBDC.23 Such stablecoins could for example create the possibility that people could use a Libra-stablecoin to transfer money abroad. With the DCEP, the PBoC intends to slow the momentum of private stablecoins. This is also an important consideration for the Western central banks.

Retention of monetary sovereignty

This is connected with the previous point. If people have easy access to a private stablecoin, it could actually in a sense reduce the role of the national currency. Something similar actually happened in Zimbabwe, where confidence in the national currency completely vanished as a result of hyperinflation and people turned en masse to foreign currencies such as US dollars and South African rand. In such a situation, the national central bank loses control of monetary conditions in its own country. Importantly, however, the DCEP could also be used by China to interfere with monetary sovereignty in other countries.

What about privacy?

The PBoC says it will respect the privacy of people and therefore the anonymity of the transactions but at the same time it says that DCEP will help it to detect illegal transactions. What this probably comes down to in practice is that people will be able to effect payments and retain anonymity between each other, but that the central bank will on the other hand be able to view the transactions. Anonymity will therefore not be guaranteed and the central bank will have much greater insight into people’s payment behaviour than it has at the moment. The DCEP will also have the status of legal tender. This means that Chinese residents will be obliged to accept the DCEP, as confirmed by various statements from the central bank on the issue (South China Morning Post, 10 November 2020). The DCEP is thus not really coming into being as a result of strong demand from the Chinese public, but it is being imposed on the population by the government. Moreover, the way the DCEP is designed, it may develop into a perfect vehicle for a quasi-command economy: it allows all transactions to be monitored, and opens the door for a retreat to a more Soviet model of banking, viz. banking under full state control.

Internationalization of the renminbi

The use of the renminbi in international transactions is still relatively limited, certainly in comparison with the dollar and the euro. But China is working steadily on increasing its usage, and even hopes that one day the renminbi can succeed the dollar as the global reserve currency. China sees the DCEP as an important vehicle for strengthening the renminbi’s international position, as foreigners will also be able to use the DCEP in transactions with China.

The benefit of this for China is that it can settle more of its international trade in (digital) renminbi. China has initially targeted Africa in this respect. Many African countries do not have fully convertible currencies and mutual trade is frequently settled in US dollars, which is expensive. China is aiming to achieve a situation in which African countries can use the DCEP not only in their trade with China, but will also use it for their domestic transactions. This is a good example of how China is aiming to position itself internationally and how various projects and institutions will cooperate under the direction of the government. The newest model of the Huawei smartphone indeed includes an app enabling payment in DCEP without the need for Internet (Eurasia). Huawei is currently already a leading telecoms provider in Africa, which gives China a head start. In other parts of the world, where Huawei is less dominant or even banned, it will off course be less simple for China to push the DCEP ahead.

Note that while China intends to strengthen its own monetary sovereignty with the DCEP, it clearly has no qualms regarding its use to undermine the monetary sovereignty of other countries. If not only a larger proportion of the trade between China and African countries but also part of intra-African trade could soon be settled in DCEP, therefore renminbi, international use of the Chinese currency will significantly increase. Note, that if a larger share of China’s international trade will be conducted in DCEP, it will also become more difficult for Chinese im- and exporters to use trade as a way to channel funds abroad. So it will held the Chinese government to reduce capital flight, although complete elimination of this phenomenon will not be possible.

Decision time: is the DCEP a wake-up call?

China is leading internationally with the introduction of CBDC, and is clearly moving in a different direction than many other countries considering a similar move. The debate in Europe is still mainly about the form the digital euro, its CBDC, should take, the question of whether there is consumer demand for it, and who should pay for it. The Chinese authorities are taking a more strategic approach, and most of all from the perspective of whether a digital currency can contribute to strengthening/entrenching China’s international position.

Assuming that the current Chinese trials are successful, we could very well see the DCEP appear as early as next year. This could be a significant step in the further movement of the Chinese economy towards cashless money. The payments system would be further strengthened by the DCEP, as this will prevent large private parties gaining a duopoly with the market power that this would entail. Financial inclusion would be improved in the underdeveloped areas, and everyone would have access to cashless money and the associated financial services that this would make possible. The black economy would be further reduced, and the Chinese government will have better insight (and control) of the payment behaviour of its citizens to an extent that we in the West would probably see as unacceptable. Lastly, the introduction of the DCEP can discourage capital flight and probably strengthen the renminbi’s international position.

All in all, the DCEP will certainly make a positive contribution to the further development of the Chinese economy. Although the DCEP looks to be less innovative than the CBDCs under consideration by the Western central banks in certain respects, the determination shown by China is undoubtedly impressive.

This Chinese resoluteness also shows that China is working very actively on strengthening the renminbi’s international position, with the central bank and companies such as Huawei working closely together to achieve this. While still a long way off, a scenario in which first parts of the African, but later maybe Asian, Latin American of even some European economies will use the renminbi for cross-border and in due course also domestic transactions is gradually becoming more plausible.

One may also expect China to try to get all countries involved in its Belt and Road Initiative to use the DCEP and therefore the renminbi. Today, the renminbi is still a small currency in comparison to the euro and most of all the dollar. But this situation could change if the DCEP becomes widely accepted. In the context of a situation in which the euro’s international position has more or less stagnated over the last decades, this is at the very least somewhat disconcerting.

Of course we may expect that, once the digital renminbi takes off and gains traction, other central banks will react strongly. Especially the US will be determined to hold on to the dollar’s international dominance. The US authorities will soon understand that a successful digital renminbi may in the long run turn out to be a larger threat to the position of the dollar than the euro ever was. The most important difference is that the euro is institutionally weak and European politicians have so far failed to use their currency as a geopolitical instrument. The Chinese government, in contrast, understand very well the power of money as a ‘peaceful’ instrument to increase international political clout.

But after all the good news may be, that the DCEP also turns out to be the important wake-up call that prompts European policymakers to finally devote serious attention to strengthening the international role of the euro. Having the second currency after the US dollar is maybe not optimal, but is not disastrous. Being third after the Chinese renminbi is a different story. In the end, money talks.

* * *

Appendix: what will the DCEP look like?

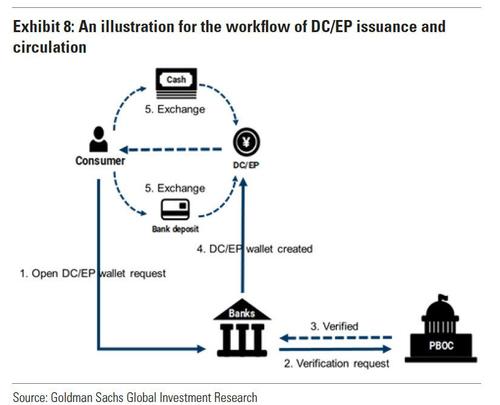

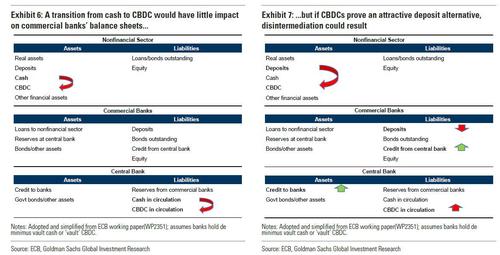

The exact design of the DCEP is still not clear. According to the BIS, the DCEP will be what is known as a hybrid CBDC. People will hold balances in their names at the central bank, but transactions will be approved using an intermediate layer of private parties (possibly including commercial banks). There will then be no direct interaction between the central bank and the account holders, but people will have an account in their names at the central bank. This would be similar to the ideas being mooted at other central banks such as the ECB and the Bank of England. Bloomberg, Blockchain News and the China Daily on the other hand describe the DCEP as a two-tier system, in which people will not directly hold accounts with the PBoC. According to these reports, in the Chinese system people will hold only a DCEP account with a bank or, more likely, with a payment service provider. These parties will in turn hold a balance with the PBoC as a liquidity reserve that exactly covers the amount of DCEP. They will also settle interbank payments in DCEP. This kind of system is also known as a synthetic CBDC (sCBDC), as people will not have their own CBDC accounts with the central bank. The PBoC will however receive regular statements of effected transactions.

If this last model is adopted, the Chinese CBDC model would be more like a full (liquidity) reserve bank than a real CBDC. A full liquidity reserve bank is a bank that would hold a 100% cash reserve with the central bank against the CBDC payment accounts held with it. But in the Chinese model, there would be no additional institution created, the existing financial institutions would offer additional accounts that would then be 100% backed by central bank reserves. Statements from the PBoC also suggest the direction is more towards a synthetic model. Technically speaking, this would represent a less innovative move than a true CBDC.

https://ift.tt/3aNxWfw

from ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/3aNxWfw

via IFTTT

0 comments

Post a Comment