How The Chinese Use Illegal Online Gambling And Tether To Launder Over $1 Trillion Yuan

It has long been known that over the past decade Chinese oligarchs who wanted to bypass Beijing's capital controls and anti-money laundering firewall, would smuggle billions of dollars outside of China by using the Macau casino money-laundering infrastructure, prompting Beijing to crack down aggressively on this popular firewall loophole, with mixed success.

What is less known is that as the capital controls game of cat and mouse escalated in recent years, so have Chinese money laundering tactics and now according to Caixin, Chinese citizens launder as much as $153 billion per year with the help of online gambling and such cryptocurrency as tether, which has long been rumored to be a key driver of upside into bitcoin (the same bitcoin we said in 2015 when it was $250 would soar thanks to Chinese attempts to circumvent the capital firewall... we were right).

Here is the story of how Beijing made this starting discovery, courtesy of Caixin:

A migrant worker from the northern Chinese city Baoding “loaned” three credit cards under his name to friends to offset 2,500 yuan ($380) of debt he owed. He never imagined he would later be arrested for illegal sale of credit cards that were used by criminal groups to launder money for online gambling.

This arrest was part of Chinese authorities’ nationwide “Card Breaking Campaign,” an operation to crack down on illicit bank card transactions and bank card sales to combat telecommunications fraud and cross-border online gambling. The campaign aims to cut off links between mobile phone sim cards and bank cards, and users who are not the registered card holders. Also included are online payment accounts such as Tencent’s WeChat Pay and Alibaba’s Alipay.

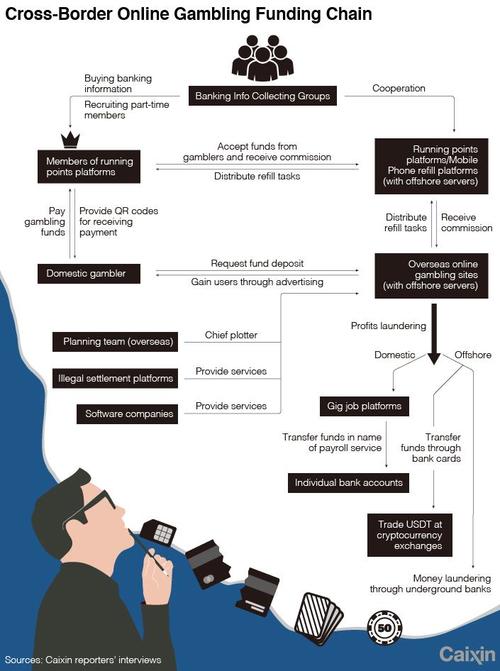

This new type of crime has created an illegitimate industry employing 5 million to 6 million people involving information technology (IT), payment settlements and operations, according to an IT department official at the Ministry of Public Security. The complex payments and money laundering system ropes in small individual players in some of China’s remotest places like the migrant worker in Baoding who loan or lease financial credentials to offshore criminal groups, which then help illegal gamblers hide money from authorities, often using Tether.’s USDT cryptocurrency.

In the first nine months of 2020, police cracked down on 1,700 online gambling platforms and 1,400 underground banks involving more than 1 trillion yuan ($153 billion) of illegal transactions, data from the Ministry of Public Security showed. That compared with 7,200 online gambling cases in 2019 totaling 18 billion yuan.

In the cross-border online gambling chain, mobile payments play an increasingly important role. As the front-runner in mobile payments, China has been aggressively promoting payments via mobile phone scans of QR codes, a type of barcode. In China, even a street food vendor owns a unique QR code for receiving mobile payments. The convenience associated with mobile payments has also attracted criminal gambling groups.

Running points platforms

As all forms of gambling are illegal under Chinese law, if a Chinese citizen wants to bet using offshore online gambling sites, the first obstacle is depositing money at gambling platforms. These operations often use leading e-commerce platforms and delivery companies to facilitate massive fund transactions disguised as legitimate online shopping deals.

For example, a Caixin reporter tried to deposit 100 yuan via online banking to a gambling site called “DreamGaming.” The transaction showed the money went to an Alipay account linked to a grocery store. That gambling site can no longer be accessed as a notice says “it contains illegal content.”

Online gambling sites usually use so-called “running points platforms” to launder gamblers’ funds to look like legitimate payments. To deposit funds, a gambler follows a payment link on a site that connects to a running points platform. This platform is like a car hailing system. A registered member of the platform will “grab orders” and upload the funds using someone else’s purchased or borrowed bank account. Then the money’s transferred to the offshore gambling site. The platforms make a commission of 2.5% to 4% on the transactions, and the members get a cut of 1% to 2%, according to police.

Chinese social media such as WeChat and Weibo often carry advertisements recruiting part-time workers. Many of these advertisements are posted by running points platforms, which would pay 500–1,000 yuan to each recruited member for their ID numbers, bank cards, mobile phone numbers and bank USB-shield, which is a security tool that looks similar to a flash disk and acts as a shield to protect user’s money in internet banking. If more information can be provided, such as a business license, business seal, business bank account and USB-shield, the price can go up to 1,500–2,000 yuan for the whole set.

To some young jobless people from smaller cities and rural areas, the chance to generate 1,000 yuan from leasing their bank accounts or QR codes is a big temptation, said an insider at a payment process company. And the more transactions go through their accounts, the more they can make in commissions. Of course, they run the risk of arrest for participating in illegal activities. In June, police in southwestern Guangxi province destroyed a cross-border online gambling operation involving 30 billion yuan of fund transfers through running points platforms.

Another channel for depositing money into online gambling sites is through mobile phone credit refills. These transactions are disguised as normal credit additions for mobile phone accounts but actually funnel money into gambling sites.

Cryptocurrency money laundering

After the running points platforms collect money from gamblers, how does the money get to the gambling operators? The traditional path is through underground banks, which facilitate illegal foreign exchange and cross-border trading. These illegal underground banks have long existed in China to help citizens transfer money out of the country to buy property abroad.

A new practice involves Tether (SDT), a cryptocurrency linked to the value of the U.S. dollar. The original goal of the cryptocurrency was to solve the problem of excessive value volatility. In 2019, USDT surpassed Bitcoin as the most-traded cryptocurrency on the market by volume.

USDT is widely used in money laundering, gambling and other illegal activities, an executive at a blockchain platform told Caixin. In October, a local branch of the People’s Bank of China in the southern Chinese city Huizhou conducted mass arrests related to cross-border online gambling, the first crackdown on activities involving USDT. In a blog post, the central bank said 77 suspects were arrested for using USDT in cross-border transactions to launder gambling proceeds worth nearly 120 million yuan.

Most USDT transactions in the Huizhou case were made on Huobi, a Seychelles-based cryptocurrency exchange founded by Tsinghua University graduate and former Oracle engineer Leon Li. Online gambling sites use gamblers’ funds to buy USDT on Huobi and then sell the cryptocurrency, thus “washing” the funds into legitimate cash flow, Huizhou police told Caixin.

China’s public security authorities ordered Huobi and other USDT exchange platforms to strengthen their anti-money laundering efforts by adding video identification verification during transactions to make sure bank cards linked to a trader’s account actually belong to the trader. But the exchanges haven’t done so. An executive at Huobi told Caixin the company completed its biggest upgrade in anti-money laundering risk control in August, without specifying the measures taken.

Huobi’s Li and Bitcoin exchange OKEx founder Xu Mingxing were reportedly cooperating with police on investigations of money laundering for online gambling.

The running points platforms and cryptocurrency exchanges place their servers offshore, increasing the investigative challenge facing police, Huizhou police said.

Difficulty to identify

For online payment platforms such as WeChat Pay and Alipay, the great challenge is to identify which users’ accounts are actually running points platforms. Looking at data of accounts that might be used by running points platforms, the amount of transactions is usually small, and many of them seem to be normal payments for consumption, said Guo Qianting, general manager of Ant Group’s anti-money laundering center. Finding running points platforms among regular users is like looking for a needle in a haystack, she said.

Another money laundering channel is gig job platforms, which provide contractors and payroll services to employers in the food delivery, ride-hailing and e-commerce sectors. More than 10,000 such platforms have emerged in China since 2018. Some of them are service providers for legitimate companies including Meituan Dianping and Didi Chuxing. But many others are used to launder money for online gambling.

In May, a local branch of Agricultural Bank of China in Xiangtan, Hunan province, detected suspicious transactions at a gig job human resources provider. The company had more than 200 million yuan of cash transactions in just a dozen days, and most of the transactions took place during abnormal business hours. Police found that the company laundered money for telecommunications fraud groups.

Last month, another gig job platform backed by Ant Group, China’s dominant online payment service provider, was investigated for suspected money laundering activities. Beijing Bujiao Technology Co. Ltd. was suspected of having falsely issued more than 1.3 billion yuan of value-added tax invoices. Some of the company’s money laundering activities involved cross-border gambling, Caixin learned.

https://ift.tt/38AftQJ

from ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/38AftQJ

via IFTTT

0 comments

Post a Comment