Liner Capacity Control And The Future Of Container Shipping

By Greg Miller, of FreightWaves,

The world’s container liner business is now so consolidated that it can deftly match vessel capacity to cargo demand. This change - courtesy of mergers and alliances - is structural, not cyclical. If there’s a single thesis for container shipping in 2020, that is it.

Assuming it’s true, there could be major future implications for the cargo shippers, yards, box-equipment owners and ship lessors who do business with liners. If liners can indefinitely calibrate capacity to cargo demand, the future newbuilding orderbook should be far less of a threat to liner profits and far less of a savior for shippers. If liners can keep managing capacity like they did this year, they may not need to lease as many containers or ships as they do now. Over the long term, it’s cheaper to own than rent.

To better understand the future implications, American Shipper interviewed Paul Bingham, director of transportation consulting at IHS Markit; Alan Murphy, CEO of Sea-Intelligence; and Stefan Verberckmoes, shipping analyst and Europe editor at Alphaliner.

Why power shifted to liners

“What the carriers have been able to achieve this year is quite remarkable,” said Bingham. “It’s a pretty finely grained management of capacity with a clear eye on headhaul rates.”

In the second quarter, liners used “blanked” (canceled) sailings to support rates. In the second half, they used “extra loaders” (unscheduled voyages) to increase revenues — until they ran out of ships to lease.

“The world of container shipping changed in 2020,” Murphy asserted. “Not because of the coronavirus but because of the response to the coronavirus. Carriers have now succeeded in what they’ve been trying to build for years: the ability to tailor supply to demand on a tactical level.

“What carriers can do now that they couldn’t do before is blank a sailing on very short notice,” he explained.

Ownership consolidation reduced the number of players. This allowed alliances to have fewer members, rendering decision-making far easier. Alliance-member executives can implement those decisions more rapidly thanks to better technology and more efficient alliances structures.

During a Q2 2020 conference call with analysts, Maersk CEO Søren Skou commented, “Since [capacity management] has worked so well for us, why should we change that? In my view, this is a structural change.”

“Capacity management is here to stay,” opined Flexport Global Head of Ocean Freight Nerijus Poskus in an interview with American Shipper last week. “Carriers are now so good at managing capacity proactively that they have an edge in the market.”

Less future risk from newbuilds

Excess newbuilding ordering has long been the bane of liner profits and a source of rate relief for cargo shippers. But today, the orderbook is extremely low, at just 8% of the total fleet. That ratio was 61% in 2007 and 19% in 2015.

“Just as carriers have become more careful about managing capacity, they will also consider managing newbuilds as part of their plan,” predicted Verberckmoes.

Murphy explained, “Now that carriers can tailor capacity to demand, there’s less need for an industry buffer. That means there’s less likelihood that carriers will go out and overorder. They’re not going to do something stupid just because freight rates are stupid.”

A step change in ship size drove the previous decade’s ordering splurge. Maersk began its 18,000 twenty-foot equivalent unit (TEU) “Triple E” newbuild series in 2011. Other carriers followed suit. But that upsizing is effectively over. “What we do not expect is another big jump in ship size in the short term. And I think that will really make a difference,” said Verberckmoes.

Liners are still placing some orders, largely for replacement as opposed to future growth. “Carriers are looking to renew their fleets and to have more environmentally friendly ships,” said Verberckmoes. “Some are thinking about replacing 8,000-TEU ships with 12,000-TEU ships, which have a better climate footprint.”

Other carriers, including CMA CGM, are building ships powered by liquefied natural gas (LNG).

“There will also be more ‘Megamax’ ships ordered in the 23,000-TEU range,” affimed Verberckmoes. “But if you look at the people ordering new ships now, like Hapag-Lloyd and ONE, these are the guys who haven’t ordered ships in a long time who are catching up with carriers who already have 23,000-TEU ships.”

Owning versus leasing containers

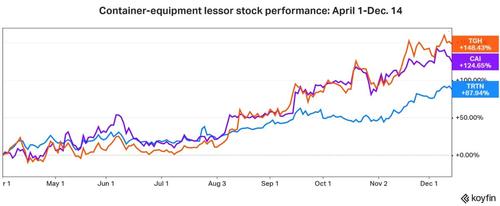

Given surging consumer demand, the world is short of containers. It is boom times for container-equipment lessors. Since April 1, stocks of Triton, CAI and Textainer are up 88%, 125% and 148% respectively.

But longer term, the new normal for liners is a mixed bag for container-equipment lessors.

On the plus side, the liners’ capacity-management acumen sharply decreases future counterparty risk. On the negative side, competition is good for lease rates and consolidation has pared the liner pool. Another negative: The share of boxes that liners lease versus own may fall as liners become financially stronger.

“Leasing is about risk management,” explained Bingham. “When times are good, you can make money on owning containers as well as vessels. If you control everything [via capacity management], you should own all your containers and own all your ships and you’re going to make money on every piece of it. But if the market turns in the other direction, liners will be caught out.”

Verberckmoes added, “In the past, carriers have had very bad results so they were obliged to sell containers and lease them back just to raise money. Now, the situation is better. So, I could imagine some carriers saying, ‘We will own more boxes rather than leasing them.’”

On Maersk’s Q3 2020 analyst call, Skou said, “We need to own more of the containers than we do. If we’re getting assets we are going to use for the full life, it’s much cheaper for us to own them.”

Maersk CFO Patrick Jany added, “For orders of new containers, in the last few years, we have focused more on leasing, and we are coming back … to owning them because it just makes much more sense.”

Owning versus leasing ships

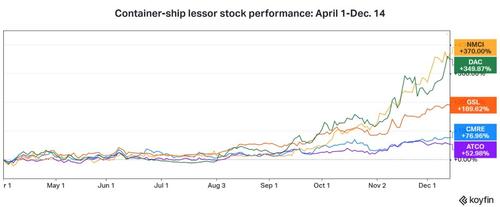

As with container-equipment lessors, today’s cargo-demand surge is a bonanza for container-ship lessors. Since April 1, the shares prices of Seaspan owner Atlas is up 53%, Costamare 77%, GSL 190%, Danaos 350% and Navios Containers 370%.

As with container equipment, the liners’ new normal is a positive for container-ship lessor counterparty risk and a negative in terms of fewer competing customers. The longer-term question is whether healthier finances will sway liners to own more of their ships as opposed to leasing them, mirroring the likely pattern on the container-equipment side.

One recent example: According to Alphaliner, Mediterranean Shipping Company (MSC) has purchased 19 secondhand ships since August with a total capacity of 102,400 TEUs for an aggregate purchase price of over $290 million. MSC could be buying ships for growth or it could be merely increasing its share of owned tonnage.

Verberckmoes does not believe liners will decrease chartered-in tonnage due to better capacity management. “There are two kinds of deals. You have carriers looking to charter ships for the next year because they need flexibility. And you have carriers chartering ships for the lifespan of the ship with an obligation to buy them at the end of the charter — which is in fact financing.

“I see more carriers doing these kinds of deals where they use charters to finance ships and a higher degree of dependency on the charter market for long-term deals,” he said.

Verberckmoes also sees continued liner demand for shorter-term charters to manage through fluctuating demand. “There will be a need because there is absolutely zero visibility on what is going to happen next year. Right now we have this e-commerce boom, which is very good for shipping. But that could end abruptly. The economy is not doing well. People will lose their jobs. There will be an economic disruption at some time.”

Different strategies for different carriers

Murphy believes liners’ future owning-versus-leasing decisions will vary from carrier to carrier. Strategies differ.

Some carriers keep their average capacity above the cargo demand volatility curve so they don’t get caught short. To do so, they accept a higher cost basis. Other carriers keep capacity lower in relation to cargo demand to reduce costs.

“Because carriers now have the ability to blank their sailings much faster than they could before, they can fit that [average capacity] line much closer to the underlying demand-volatility line,” explained Murphy. This might convince liners that traditionally keep capacity above demand to own more ships as opposed to leasing them, allowing a lower cost basis.

“Overall, if you can match supply with demand on a much more granular level, and you have good ways to minimize the cost of laying up vessels that you don’t need on any given week [due to blank sailings], you might lean more towards ownership,” he said.

Ways this could this go wrong for liners

Bingham remains skeptical that liners can hold the line over the long term when it comes to capacity management. “All of these changes are predicated on continued carrier discipline on capacity deployment. If that breaks down, then so do all of these premises,” he noted.

“In the past, when there were too many ships and you had [lessor-owned] ships going off hire, you saw this competition and downward spiral on charter rates, trying to tempt somebody to jump in, to break somebody away and behave differently,” said Bingham.

“At some point, we’re not going to be able to sustain the current consumption,” he continued. “When that happens, I’m not convinced that all of the participants in all of the alliances won’t succumb to temptation.”

According to Murphy, “This time, it does seem like carriers have learned their lesson. But if there was one thing that I would have put money on during the past 20 years, it was carriers’ ability to grasp failure from the jaws of victory. They have been really good at that.”

Future government intervention?

Beyond collapsing cargo demand, liner capacity discipline faces at least two other future risks. One is China. At some point in the future, some market participants see a possibility that Chinese shipping could go its own way. State-owned companies could place massive orders at Chinese yards and go for market share.

The other risk is that regulators in China, the U.S., the EU and/or Korea might intervene.

“There are certainly enough shippers banging on regulators’ doors right now,” said Bingham. “At some point, politics is going to play out in this in a way that liners might not fully appreciate.

“If you are able to control your pricing through capacity management, that only works until the point of sovereign intervention.”

https://ift.tt/2KXpQ9p

from ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2KXpQ9p

via IFTTT

0 comments

Post a Comment