Steve Keen: This Ain't Your Daddy's Inflation – Part 1

Authored by Steve Kenn via The Epoch Times,

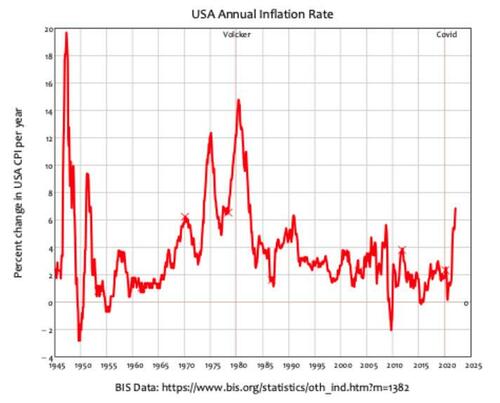

After a long period of being low and even negative, inflation is now higher than it has been in almost 40 years. Though still well short of the twin peaks of 1975 and 1980, it is the fifth-highest rate recorded since the end of WWII, and it is still rising.

But it ain’t your Daddy’s inflation: what’s driving it is very different to what drove the inflation of the 1970s. Unfortunately, the 1970s experience changed economic theory for the worse, and that theory will guide how the Federal Reserve tries to tackle today’s inflation. It won’t end well. To explain why, I need to use a lot of figures (and a lot of words), so brace yourself.

Figure 1 shows the entire history of post-World War II inflation in the USA. There were four major peaks before today’s spike, with the first two driven by Wars (the end of WWII and its price controls, and the boom in commodity prices during the Korean War). The second two, in 1975 and 1980, created modern economic theory, because they appeared to overthrow the “Keynesian” argument that fiscal policy could control both inflation and unemployment.

Figure 1: Chart showing annual change in the USA consumer price index since 1960. (Steve Keen)

“Keynesians” asserted that there was a tradeoff between inflation and unemployment: unemployment could be lowered by expansionary fiscal policy, but at the price of a higher rate of inflation. The “Keynesian” belief was that there was a negative relationship between inflation and unemployment: if inflation went up, then unemployment would go down. This was called the “Phillips Curve,” after the New Zealand engineer-turned-economist Bill Phillips, who wrote a famous empirical paper on inflation and unemployment called “The Relation between Unemployment and the Rate of Change of Money Wage Rates in the United Kingdom, 1861–1957”.

The killer blow to “Keynesian” economics was the coincidence of rising inflation and rising unemployment between late 1973 and 1975. This was dubbed stagflation, and because this was impossible according to “Keynesian” theory, Milton Friedman’s Monetarism won an intellectual battle within economics, and supplanted “Keynesianism.”

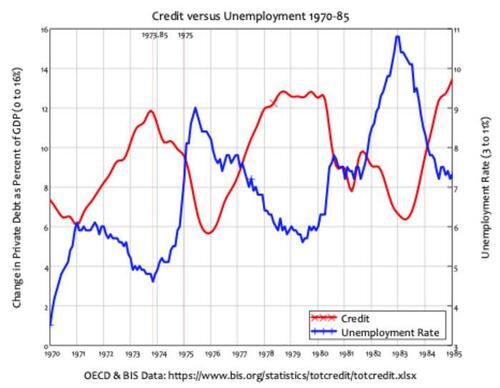

Figure 2: Chart showing rising unemployment and inflation between 1973 and 1975. (Steve Keen)

Are you sick of the inverted commas around “Keynesian” yet? Good. They’re there to make the point that this wasn’t Keynes’s theory at all, but rather how it was caricatured by the anti-Keynesian economist Milton Friedman. Trusting Friedman’s explanation of Keynesian economics is like trusting the fox’s account of why the chickens in the henhouse died.

The true inheritor of Keynes’s mantle was the renegade economist Hyman Minsky (who was the chief inspiration for my work), and he argued that credit was the main factor behind the economy’s ups and downs. When people and firms are borrowing heavily, the economy will boom, and when they borrow less or repay debt, the economy slumps. The important link, in Minsky’s genuinely Keynesian economics, is between credit and unemployment, not between inflation and unemployment.

That’s obvious in the data: when credit (the annual change in private debt) is rising, unemployment falls; when credit is falling, unemployment rises. The real cause of the “stag” half of stagflation was the decline in demand as credit collapsed from 12 percent to 6 percent of GDP between September 1973 and 1976.

Figure 3: Chart showing the inverse relationship between credit (the change in private debt) and unemployment. (Steve Keen)

The “flation” bit came from two unrelated factors:

-

the booming economy that preceded the crash of 1973, as credit doubled from 6 percent to 12 percent of GDP between 1971 and September 1973;

-

and the Yom Kippur War, which occurred in October 1973.

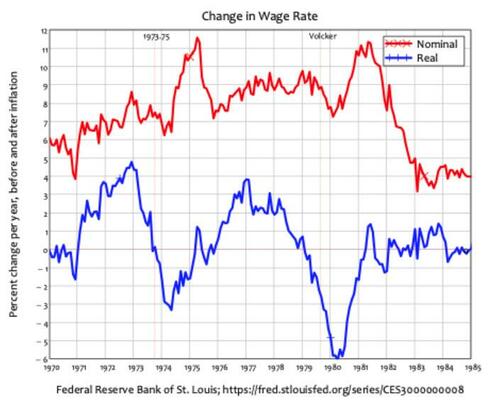

It may be hard to believe from today’s perspective, but workers had both strong trade unions and substantial bargaining power in the 1960s. Unemployment fell below 4 percent in 1966 and remained there until early 1971. It rose substantially—from 3.5 percent in 1970 to 6 percent in 1971—but fell down to a low of 4 ¾ percent in late 1973, just after the credit bubble started to burst. Workers and unions had no way of knowing in advance that this was the end of the good times—unemployment did not fall below 4 percent again until a few months in 2000, and then again before and after the COVID-19 recession—so they continued to bargain for high wage rises, which employers passed on to consumers in price rises.

Figure 4: Chart showing the annual change in nominal and inflation-adjusted wage rates. (Steve Keen)

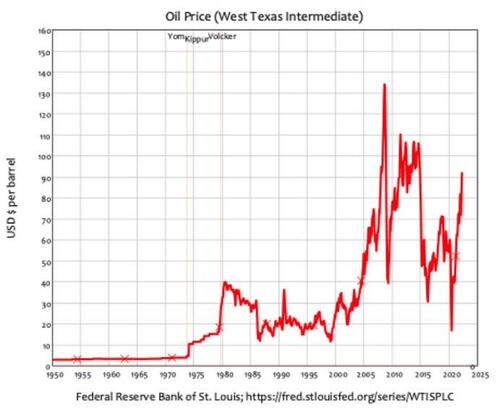

A second factor, which had never happened before, caused price rises well above the rate of wage growth: rising oil prices. Before 1973, oil prices were largely set by Big Oil: the western-owned oil companies that dominated oil drilling around the world, including in Arabian countries. They paid the oil-producing countries a pittance in royalties, and prices were low and stable—as is vividly obvious in Figure 5, where the price is a flat line between 1950 and 1973. The resentment at being paid low prices for their vital commodity motivated oil-producing countries to form OPEC (the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) in 1960.

After the defeat of the Arab armies in the Yom Kippur War, OPEC launched an embargo on oil exports to the USA, which caused the oil price to increase by 250 percent, from $4.30 to $10 a barrel, in just one month.

Figure 5: Chart showing the nominal price of West Texas Crude Oil. (Steve Keen)

The coincidence of rising prices and rising unemployment therefore does have a Keynesian explanation, and the capacity for private banks to create money and additional demand by making loans plays a crucial part in it. But this wasn’t part of Friedman’s thinking at all. To him, the government was the only creator of money in the economy, and—to caricature Friedman, though more accurately than he caricatured Keynes—inflation was caused by “too much money creating too few goods.”

Friedman argued that the economy had a tendency towards what he dubbed the Non-Accelerating-Inflation-Rate-of-Unemployment—or NAIRU for short. This was set by “real” factors—people’s willingness to undergo the disutility of work, in order to receive the utility of income (in the form of either wages or profits), where this utility was measured in their physical level of consumption and not money.

A rising money supply could, however, stimulate more work, by temporarily fooling people into believing that real demand was higher than it really was: if the amount of money rose faster than the economy grew, people would initially mistake this for a higher rate of real growth in demand. Friedman then used the idea of a short-term negative relationship between unemployment and inflation to assert that this lower level of unemployment would cause a higher level of inflation.

The higher inflation would then reduce real incomes to where they were before the excessive increase in the money supply occurred. People would then come to expect this higher level of inflation to persist, while the economy settled back into its full-employment equilibrium.

Therefore, the long run effect of trying to stimulate the economy by increasing the money supply would be to increase people’s “inflationary expectations,” while leaving the level of economic activity constant at its long run equilibrium level. If the government wanted to drive the unemployment rate below the natural rate, it would have to increase the money supply even faster: hence trying to keep the unemployment rate below the natural rate required an increasing rate of growth in the money supply, and caused not merely a higher rate of inflation, but an accelerating rate of inflation.

This meant that what Friedman dubbed the Long Run Phillips Curve was vertical: the relationship between unemployment and the rate of inflation was a vertical line. The only desirable point on this curve from a social welfare point of view was where inflation was zero: this was the “Non-Accelerating-Inflation-Rate-of-Unemployment.”

So where does that leave us?

-

Hyman Minsky’s explanation of what caused the stagflation of the 1970s - a credit bubble bursting when the economy was absolutely at its peak caused the stagnation, while high wage and oil price rises caused the inflation.

-

And the essence of Milton Friedman’s very different explanation: that it was due to the government trying to push the unemployment rate below the natural rate by increasing the money supply too quickly.

I’ll go into Friedman’s argument in more detail below, not for its historical interest, but because an essential part of it—the concept of “inflationary expectations”—still plays a major role in how Central Banks think they can control the economy.

One key belief of Friedman’s was that the economy had a natural rate of unemployment, to which it would return after any shock. Another was people held money primarily to make transactions, so that the cash people held was proportional to the level of output.

If we identify the money in our hypothetical society with currency in the real world, then the quantity of currency the public chooses to hold is equal in value to about one-tenth of a year’s income, or about 5.2 weeks’ income. That is, the desired velocity is about ten per year.

Friedman treated the velocity of money as a constant, so if the amount of money rose, then so would the level of transactions. He imagined an economy with a constant population, and no technological progress, in which there were 1,000 $1 bills:

All money consists of strict fiat money, i.e., pieces of paper, each labeled “This is one dollar.” To begin with, there are a fixed number of pieces of paper, say, 1,000.

Given the 10 to 1 ratio between the money stock of $1,000, and the level of economic activity, this meant that, in equilibrium, GDP would be $10,000 per year. Then Friedman imagined an event that would disturb this equilibrium. Have you heard the phrase “helicopter money?” It made its first appearance in this paper: The Optimum Quantity of Money by Milton Friedman.

Let us suppose now that one day a helicopter flies over this community and drops an additional $1,000 in bills from the sky, which is, of course, hastily collected by members of the community.

This would increase the amount of money people held from 1/10th of a year’s income to 1/5th. Since people were now holding twice as much money as they wanted, they would attempt to get rid of the excess by spending more. This could cause a temporary increase in real activity as people interpreted the increase in money demand as an increase in real demand, but ultimately the economy would settle back into its long-run equilibrium. Prices would double, but there would be no change in real output or employment.

Friedman extrapolated this to a continuous increase in the money supply by imagining a continuous stream of helicopters.

Let us now complicate our example by supposing that the dropping of money, instead of being a unique, miraculous event, becomes a continuous process, which, perhaps after a lag, becomes fully anticipated by everyone. Money rains down from heaven at a rate which produces a steady increase in the quantity of per cent per year money, let us say, of 10 percent per year.

Friedman reasoned that this would result in prices rising at 10 per cent per year. The economy would be in long run equilibrium, with supply equal to demand in every market, but with rising prices—because of “inflationary expectations.” This was a crucial part of Friedman’s argument: prices weren’t rising because of demand exceeding supply, but because of inflationary expectations.

One natural question to ask about this final situation is, “What raises the price level, if at all points markets are cleared and real magnitudes are stable?” The answer is, “Because everyone confidently anticipates that prices will rise.”

In our example, prices rise, though markets are continuously cleared, because everybody knows that they will. All demand and supply curves in nominal terms rise at the rate of 10 percent per year, and so do the market-clearing prices.

The key to getting inflation down was therefore to reduce “inflationary expectations.” Inflation was occurring simply because people expected it, and put their prices up by that much every year—both the prices they charged for their own services, and the prices they were willing to pay for others.

That could be done simply by reversing the previous policy: reduce the rate of growth of the money supply. This would initially cause a small recession, but once people realized that only nominal—rather than real—demand had fallen, the economy would converge back to the equilibrium rate of growth with a lower level of inflationary expectations. Relatively painlessly, the economy could be restored to a low inflation environment.

This is the policy that Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker put into motion in 1979. He put up the Federal Funds Rate to 20 percent in an attempt (to quote Volcker from the Fed’s minutes in his first meeting as chairman) to reduce inflationary expectations (pdf).

I do believe that we have to give some attention to whether we have the capability, within the narrow limits perhaps in which we can operate, of turning expectations and sentiment. I am thinking particularly on the inflationary side. [Can we] restore the feeling that inflation will decline over a period of time and that that’s a prime objective of ours?

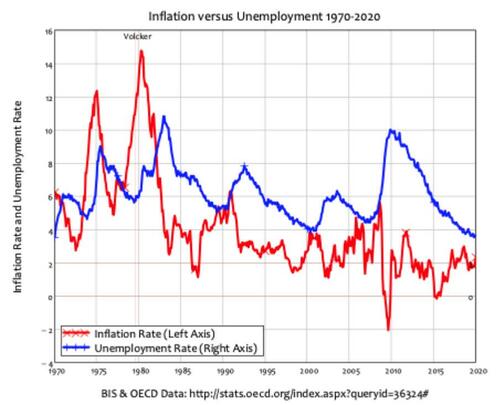

Volcker’s actions did cause the rate of inflation to fall. However, this was not via a relatively painless fall in “inflationary expectations,” but by a savage recession, the deepest the USA had experienced since the Great Depression. Inflation fell from 15 percent at its peak to below 2 percent by 1987, but unemployment rose just as sharply, from under 6 percent when Volcker started to increase interest rates to almost 11 percent when inflation had fallen to just above 2 percent.

Figure 6: Chart comparing inflation to unemployment for the 50 years before COVID. (Steve Keen)

The economic collapse took the wind out of both wage rises, and the price of oil. Wage rises, which peaked at 11 percent per year in 1981, fell to 4 percent per year in 1983. Oil prices, which had risen from $15 to $40 a barrel in 1980, fell gradually to $30 in 1985 and then plunged to just $12 a barrel in 1986. In addition, the negative relationship between unemployment and inflation—the disappearance of which between 1973 and 1975 had played such a large role in getting Friedman’s theory accepted—was back.

To be continued...

https://ift.tt/O4ZKy8E

from ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/O4ZKy8E

via IFTTT

0 comments

Post a Comment