Mystery At The Midterms: What Really Happened To The Red Wave?

Authored by James E. Campbell via RealClear Wire,

It was shocking, but even more puzzling. A consensus of commentators, pundits, pollsters, handicappers, and election forecasters (myself included) expected a strong Republican showing in the 2022 midterm – gains of anywhere from about 20 to more than 40 House seats and even small gains in the Senate and in governorships, despite defending majorities of seats up for those offices (21 of 35 Senate seats and 20 of 36 governorships).

Several observers predicted Republicans to win more House seats than at any time since the 1920s. A Republican red wave was anticipated. The only serious question was how big it would be. But what hit shore on Election Day was more of a weak ripple than a powerful wave, leaving behind the question: What caused this November surprise?

A Deep Dive Into the Red Wave

What follows is an investigation into what happened to that anticipated red wave. Since the analysis is involved and lengthy, this synopsis is provided up front. Both real and publicly perceived conditions before and up to Election Day provided all the ingredients for a very good Republican year. That red wave had formed, was within sight and headed to shore, but never made it. What happened? Extending the wave metaphor, Democrats constructed what amounted to a breakwater, effectively fending off the wave. It was particularly successful in about eight states with crucial tight races for statewide offices. Democrats built their breakwater from easy mail-in voting provisions, effective mobilization programs, and massive campaign spending to fuel the push. It succeeded because Republicans failed to counter it.

Of the many explanations offered for the Republicans’ stunning shortfall, this is the only one consistent with all the evidence, with the many forecasts and projections, and with established theories of midterm elections that could not have possibly anticipated the breakwater. The surprising result of the 2022 midterm was not a consequence of vox populi. It was the result of mobilization-friendly electoral systems, organization, and lots of money – essentially 21st century machine politics. That’s where this is headed; on to the evidence and analysis.

Conditions for a Red Wave

Everything pointed to a big Republican year. Everything. Every indicator of politically salient national conditions – the economy, inflation, energy prices, interest rates, and crime rates – read in their historical perspective strongly favored the Republicans. Other contemporary conditions also favored them, from the unimpeded influx of millions of illegal immigrants to destabilized international conditions and the humiliating debacle of a botched withdrawal from Afghanistan. The Democrats could hardly have found themselves in more dire straits.

And that is not all. According to national polls conducted by dozens of reputable survey organizations over many months leading up to Election Day and beyond, Americans consistently gave Democrats poor marks.

Three broad-based public opinion readings summarize the political climate. First, President Biden was widely and deeply unpopular. His average job performance approval rating at Election Day stood at only 42% and had remained this low for several months. He sat near the bottom of the rankings of post-World War II unpopular presidents at their midterms. About 45% strongly disapproved of his job performance. Opinions on specific issues were no better. Second, most Americans thought the nation was headed in the wrong direction (68% in RCP’s average and about 75% in the exit polls). Third, the same three-out-of-four felt the economy was in very bad shape, describing it as “not so good” or “poor” in the exit polls. There was no good news for Democrats anywhere.

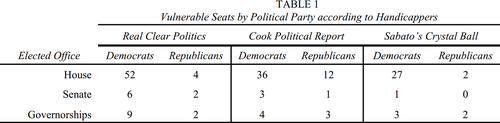

And even that is not all. These poor national conditions for Democrats shaped individual congressional and gubernatorial races. Hundreds of polls conducted in competitive contests as well as the assessments of non-partisan election handicappers found Democratic prospects to be bleak. Table 1 summarizes pre-election, end-of-campaign assessments by three non-partisan organizations (RealClearPolitics, The Cook Political Report with Amy Walter, and Sabato’s Crystal Ball) of each party’s seats seriously at risk of being flipped (rated as “toss-ups” or regarded as leaning or likely to be won by the opposing party).

In Senate and gubernatorial races, Republicans had only small advantages, largely because they already safely held so many seats at risk in the election. In the House, however, Republicans were positioned for big gains. By these assessments, there were two to as many as four dozen more seats in trouble (toss-ups or worse) for Democrats than for Republicans. Yes, the Republican House advantage could be measured in multiple dozens of seats.

In short, there is plenty of evidence that conditions, both real circumstances and public perceptions, provided an ample basis for a red wave. There is plenty of evidence, too, including polling and expert election handicapping of state and district races, that the red wave had formed.

But the wave never made it to shore. Rather than picking up 20 to 40 seats and a large House majority, Republicans gained an anemic nine seats and a slim majority, exactly as small as the Democrats’ displaced majority. Democrats held more than three-quarters of their toss-up seats (24 of 29 in RCP, 20 of 26 in Cook, and 14 of 17 in Sabato before their November 7 toss-up projections). And rather than picking up a few more Senate seats to regain a Senate majority and a couple of governorships, Republicans lost one Senate seat and a net of two governorships. The midterm results inexplicably defied all the historically dominant influences on midterm elections and all the expectations built on them. It also has had and continues to have enormous consequences.

Normal? Not So Much

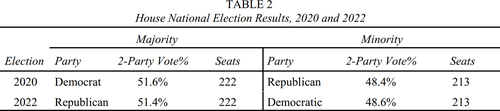

In a superficial sense, this surprising election might oddly look normal in light of two basic historical facts about midterms. First, in the 20 national congressional elections since 1984, 12 (60%) produced seat changes in only single digits. Second, in the 28 midterms since 1912, the presidential party lost seats in all but three (89%). Based on this, a nine-seat loss in the House for the Democrats looks par for the course. In addition, the 2022 House result was simply the mirror image of the election two years earlier. In both elections (see Table 2), the party receiving the majority of the national House vote received about 51.5% of the two-party vote and won exactly 222 House seats.

But 2022 looks normal only on the surface. The missing red wave is not about how votes translated into seats. It is about how narrow the vote division itself was. In these terms, 2022 is quite abnormal. With all the advantages of national conditions and public opinion auguring a strong Republican year, Republicans would normally have received a significantly greater share of the two-party vote. Why wasn’t their share of the vote much larger than it was?

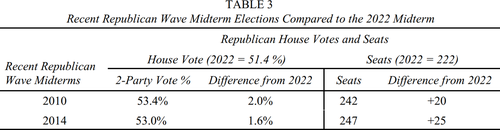

A comparison with the two recent Republican waves, the midterms of 2010 and 2014, puts the shortfall of the Republican 2022 vote in perspective (Table 3). After 2010 and 2014, Republicans held 242 and 247 seats, respectively. These were two of the three best House outcomes for Republicans in the 46 elections since 1932 and a far cry from the 222 seats won in 2022. Though these seat differences between 2022 and prior wave elections are large, the vote difference is not as great as one might imagine. The Republican national vote in 2022 is only 1.6 points lower than the vote in its 2014 wave and only 2.0 points lower than in its 2010 wave. Now moving the national vote about two points or a bit less is not an easy matter; on the other hand, it might not be a Herculean feat either. And getting even halfway there would have made a big difference. Recognizing this expands the field of plausible reasons why the Republicans fell so far short of expectations.

Let the Speculation Begin

Why did the election fall so far short of expectations for Republicans? It seems everyone has an opinion on the matter. In general terms, the Republican shortfall has been broadly interpreted as a repudiation of Republicans, a vindication of Democrats, or a mixed-bag affirmation of the status quo.

Out of the file of more specific speculations, the eleven most common explanations of the Republicans’ disappointing outcome appear to be: (1) voters rejected the party of Trump and his selected MAGA-supporting candidates; (2) voters rejected Republican extremism; (3) voters rejected Republican candidates who were “election-deniers” deemed a “threat to democracy”; (4) Republicans failed to reach out to political moderates; (5) Republican Party leadership failed to communicate a memorable, specific, and positive message to voters; (6) Republicans nominated many flawed candidates; (7) economic conditions were not as bad as many believed; (8) many swing voters considered Biden’s record and policies to be “comforting”; (9) young first-time Democrat-inclined voters surged to the polls to support Biden’s student debt “forgiveness” policy; (10) young unmarried women surged to the polls to vote against Republicans because of the Supreme Court’s decision on abortion; and (11) high expectations of large Republican gains failed to consider the constraints of severe polarization, gerrymandering, and the “patchwork” of differences in local political conditions.

Are these opinions plausible explanations for the red wave unexpectedly shrinking into a red ripple? Are they consistent or reconcilable with the evidence? The answer is that none of these would-be explanations fare well with the evidence, either with evidence specific to their claims or evidence of a more general nature.

Evidence: The Particulars

Most of these are challenged directly by inconsistencies with the facts. Without getting bogged down in evaluating each individual speculation, what follows are examples of their problems and an overall reason why none of them solve the puzzle.

First, there is the go-to claim that “Trump did it.” But while 28% in the exit polls said their House vote was a vote against Trump, another 32% said their vote was cast against Biden. More importantly, there is no reason to think views about Trump became any more negative at the very end of the campaign, thereby blocking the red wave. Views about Trump and MAGA are about as set in stone as, well, stone. Even the FBI’s unprecedented raid on former President Trump’s Mar-a-Lago home in early August, three months before Election Day, left opinions about where they had been. Opinions about Trump were 54% unfavorable on the day of the raid and 54% unfavorable on Election Day.

Related examples involve the idea that the shortfall involved voters turning away from Republicans because they were thought to be extremists and threats to democracy. The exit polls and the AP-VoteCast surveys, however, found the parties were about equally likely to be seen as too tolerant of extremists or as threats to democracy and, again, there is no reason to think these moved more against Republicans late in the campaign.

Other speculations concern supposedly unanticipated turnout surges of specific pro-Democratic groups. The exit polls, however, show no turnout surges of young voters, or first-time voters, or unmarried women. According to the exit polls, each of these groups comprised the same or lower percentage of voters in 2022 than in either of the two previous elections.

As to the status quo forces of polarization, gerrymandering, and local political conditions sapping the strength of the red wave, we should remember these factors did not stop the Republicans’ powerful waves of 2010 and 2014 or the Democrats’ strong wave in 2018. Polarization, gerrymandering, and local political differences are overrated as impediments to national wave elections. They are more speed bumps than walls. Recall, too, from Table 3 that the difference between a ripple and wave is a mere two points or less of the national vote.

The Achilles’ heel of all these explanations is timing. Any effect these factors might have had on voters would have been fully incorporated into polls and projections well before Election Day. If Republican candidates were seen as highly flawed, extremists, or threats to democracy, why wouldn’t these opinions have affected polls and projections long before votes were cast? The same could be said about flawed Republican campaign messages.

There is no reason to think that voters would have held back their reactions until the campaign was over. To the extent they were real and made a difference to voters, these factors were not exactly late-breaking news to anyone (even the Supreme Court’s controversial Dobbs decision on abortion was handed down in late June, more than four months before Election Day), and there is no reason to think voters had been shy about expressing their opinions about them before Election Day. As such, they do not explain why the outcome differed so greatly and so abruptly from strongly anchored expectations of a red wave. As a group, each of these opinions about what caused the November surprise falls flat.

Evidence: The Fundamentals

Beyond the evidence specific to the claims, any explanation for the Republican shortfall should be consistent with – or reconcilable with – the stability of both fundamental national conditions and public opinion.

First, with one possible exception (to be discussed later), the fundamental politically important real conditions of the nation ran strongly and consistently against the Democrats from early on to Election Day and after. From the economy to international politics to crime, across the board conditions were and remained consistently bad news for Democrats. There was plenty of time for these influences to have been fully incorporated into voter decisions long before balloting began, even with very early voting. The direction and the stability of these conditions rules them out as causes of the red wave’s disappearance.

The only possible exception to stable “facts on the ground” favoring Republicans is the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision overturning Roe v. Wade. That ruling immediately set off a firestorm of outrage among pro-choice advocates and undoubtedly activated some Democratic voters. (A post-election Economist/YouGov poll indicates abortion was the most important problem to 17% of reported voters, but only 9% of their full sample that included non-voters.)

The problem is that the highly publicized Dobbs decision was handed down in late June and a draft of the decision had been leaked about seven weeks earlier, in the first week of May. The controversy was in full fury more than five months before Election Day and several months before voting in states offering early voting options. Any effect the abortion issue had on vote choices or turnout decisions of potential voters had more than enough time to be reflected in polling and election expectations well before Election Day or early voting. As such, like the many other existing stable conditions of the election, it does not explain the November surprise.

Second, public opinion expressed in various ways about national conditions, leaders, and candidates in dozens of polls conducted over many months also ran strongly against the Democrats and was quite stable. According to Gallup, in July only 14% thought that the economy was “excellent” or “good.” In November it was 15%. Again in Gallup, in August only 25% thought the economy was getting better. In November it was 24%. According to the RCP poll averages, from mid-September to Election Day, roughly two-thirds of Americans (64% to 68%) thought the nation was “on the wrong track,” and only about a quarter (24% to 28%) thought it was moving in “the right direction.” There was no discernable trend. President Biden’s approval ratings remained poor throughout the campaign, at Election Day and even after. His RCP approval ratings from Labor Day to Election Day hovered within one point of 42%. His performance ratings on many issues and his personal favorability ratings were as dependably low.

The one notable exception to the constancy of public opinion was the polling numbers on the House generic (party) vote. The generic poll division did change over the course of the campaign; however it was in the wrong direction to account for a Republican shortfall. As Election Day approached, the generic poll did not become more favorable for Democrats. To the contrary, it grew more favorable for Republicans. According to RCP’s generic poll average, the parties were tied in the generic poll in late September, but by Election Day, Republicans had a 2.5 percentage point lead.

Though not a change in public opinion per se, there was another indicator of late campaign movement – the handicapping of the races. Just as with the generic polls, these ratings changes showed movement toward the Republicans – in the Cook Political Report and RealClearPolitics’ House ratings from mid-October to Election Day. In the last week of the campaign, in making calls on House toss-up races, Sabato’s Crystal Ball made 29 ratings changes. The overwhelming number of these (24) favored Republicans.

What Changed? Nothing.

Nothing moved the fundamental public opinion “needle” in the last few months of the election, since the “needle” was pretty much unmoved. Any hint of a slight movement (the generic polls and race ratings) favored Republicans, not Democrats. Even late-deciding voters, according to both the exit polls and AP-VoteCast, split in favor of the Republicans. Yet while the views of the American public undergirding expectations of a resounding red wave did not appreciably change in the last months of the campaign, the election’s actual outcome for Republicans fell far short of expected.

This would be remarkable in normal times, but is especially so now with so much early and mail-in voting. With nearly 60% of votes nationally cast before Election Day, either by early in-person voting or by mail, it is less plausible than ever that any of these considerations would not have already influenced polls and expectations and could have produced the surprising outcome. With so much early voting, a substantial number of votes had already been cast when many “pre-election” polls were still being conducted and expectations formed! One would surely have expected these polls to reflect the crucial opinions behind votes not only intended, but already cast. Under these circumstances, the discrepancy between the expected red wave and the red ripple outcome becomes even more mind-boggling.

All grounds for expecting a big red wave remained intact to Election Day. What changed in public opinion to account for the startling difference between the midterm’s widely expected outcome and the actual outcome? Nothing. The implication of this is inescapable: looking to public opinion for the cause of the November surprise is looking in the wrong place.

Although we do not know from this evidence what caused the Republican shortfall, we do know what did not cause it. And we know that its cause does not depend on changes in public opinion, changes that did not occur. So, if changes in public opinion did not cause the November surprise, what did? What’s left?

Evidence: State Differences

Fortunately, additional evidence may shed light on what happened to the red wave. This evidence is drawn from the differences between pre-election poll and actual vote spreads between candidates in competitive statewide races (Senate and gubernatorial contests).

The overall poll spread in a race is the RCP average of the spread in polls (differences between the candidates’ poll percentages) conducted near the end of the campaign. It is usually based on three to six different surveys. Numerous polls were reported and monitored for competitive statewide races in 21 states. These included 12 Senate and 16 governorship races (with seven states having what RCP identifies as “top” races for both offices). Of these, 24 races in 17 states had enough late-conducted polling to determine discrepancies between meaningful pre-election expectations and the results of these elections.

The mysterious Republican shortfall, differences between expectations (poll spreads) and outcomes (vote spreads) in these statewide races, varied considerably. While the consequences of the red wave’s disappearance are naturally interpreted as national in scope, its effects and likely causes were not uniformly national or anywhere near it. Determining where the red wave substantially fell flat may provide important clues as to why it fell flat.

The discrepancies between expectations and outcomes in the states essentially sort into two groups and one outlier. The outlier is Florida where Republicans exceeded expectations. Both Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis and Sen. Marco Rubio finished with vote spreads seven to eight points greater than the polls indicated, while Republicans netted the four House seats they were expected to gain.

As a leading contender for the 2024 Republican presidential nomination, DeSantis built a massive war chest for his 2022 reelection bid. With contributions in excess of $200 million and expenditures over $122 million, DeSantis outspent his Democrat opponent Charlie Crist, 4-1. Though Rubio was greatly outspent by Democrat Val Demings (about $50 million for Rubio to $80 million for Demings), the DeSantis juggernaut established a favorable climate for all Florida Republicans. Combined with generally positive grades for handling Hurricane Ian’s devastation in late September, support for Florida’s Republican slate grew throughout October.

Beyond Florida, the first broad group of races consists of the large majority of states whose results were pretty much in line with the polls and expectations, with some edging a bit more than expected toward the Democrats. No big surprises here.

A second group is where the action is and where clues to the red wave mystery might be found. These are the eight states in which Democratic candidates most clearly outperformed their expectations, where the November surprise was most clearly indicated. For brevity, these are “The 8 States.” They are Arizona, Colorado, Michigan, Nevada, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, Washington, and Wisconsin. These states held elections for seven Senate seats (the exception being Michigan), seven governorships (the exception being Washington), and 70 House seats. Of the two statewide offices, each of the seven Senate races and four of the seven governorship races were very competitive (the exceptions being the fairly safe Democratic governorships in Colorado and Pennsylvania and the safe Republican governorship in New Hampshire). Of the 70 House seats, RCP’s pre-election rating counted 26 (37%) as competitive (toss-ups, leaning, or likely for either party).

Like the national congressional vote, when the outcomes of the elections in The 8 States are examined, it first appears nothing happened. And, in a sense, that is true. Democrats came out of the midterm gaining one Senate seat in these states, from a 5-2 split to a 6-1 split. The Democrats had the same 5-2 lead in the governorships they had before the midterm. And only reapportionment changed the collective division of House seats a bit from a 41-31 split in the Democrats’ favor to a 39-31 split in their favor. There was barely any change. But what did not change is what is important. Republicans did not win the share of these elections they were expected to win. As in the Sherlock Holmes mystery story “Silver Blaze,” this was the dog that didn’t bark, but was expected to.

Democrats in The 8 States did surprisingly well. Without exception, each of the 14 Democratic Senate and gubernatorial candidates fared better in the election than in late pre-election polls. Most won by larger vote margins than poll margins – several by much wider margins – and the few Democrats who lost, lost more narrowly than the polls had indicated. In the very competitive statewide races, generally rated as toss-ups or leaning races, Democrats won 9 of 11 (82%). The only Republican candidates to survive were Ron Johnson in Wisconsin’s Senate race and Joe Lombardo in Nevada’s gubernatorial election.

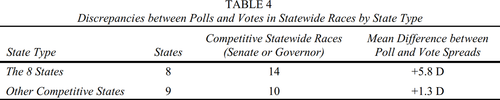

The best evidence of the concentration of the Republican shortfall in The 8 States is a comparison to the other states. Dealing first with Senate and governor’s races, the poll versus vote discrepancy in The 8 States was typically far greater than in the other states having comparable data. In the 14 statewide elections in The 8 States, Democratic candidates, on average, exceeded their spread in the polls by 5.8 points. In contrast, in 10 statewide elections in the nine other states similarly monitored by RCP, the vote for Democratic candidates ran only 1.3 points better than the poll spreads (see Table 4). Both sets of Democrats outperformed their polls (and Republicans fell short of theirs), but those in The 8 States typically gained about 4.5 points more ground on their Republican rivals.

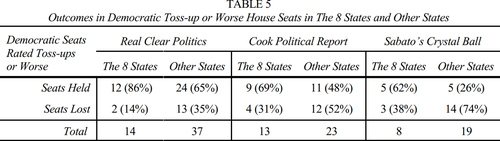

The difference shows up in House elections as well. As in the statewide races, the best evidence of The 8 States difference in House elections is to compare what happened to them to what happened elsewhere. Unfortunately, we do not have extensive and comparable polling on individual House races, but what we do have are the non-partisan election handicappers who rate the competitive outlook in every congressional district. The election outcomes of Democratic seats in trouble, according to three prominent handicappers (RCP, The Cook Political Report, and Sabato’s Crystal Ball) in The 8 States and in the rest of the nation are presented in Table 5. Too few Republican seats were rated in trouble (toss-ups or worse) to examine.

If Democratic House candidates in The 8 States enjoyed the advantages of Democrats above them on the ticket, then more of them in peril should have held their seats than similarly threatened Democrats in the other states. That is exactly what Table 5 shows. For the two sets of states, it reports the won-loss rates of Democrats with toss-up or worse election prospects as assessed by each of the three election handicappers. While each has its own evaluation and threshold for its ratings, one common fact is glaringly evident: Democrats in trouble in The 8 States had a far higher chance of surviving the election than Democrats in trouble elsewhere. From the Republican vantage point, their prospects for picking up seats were much more likely to be thwarted in The 8 States than in other states. The survival rate difference between these states for Democrats in trouble was over 20 percentage points in each of the independent ratings (21 points in both RCP and Cook, and 36 in Sabato). The results reaffirm the surprisingly strong advantages Democratic candidates had in The 8 States.

The evidence unequivocally supports the distinction between The 8 States and the other states. Whatever happened to the red wave happened substantially, though not entirely, in these eight states. “Not entirely” is an important caveat. These are the states in which the election’s outcome most clearly and substantially departed from expectations, but a few others were on the cusp. That the Republican shortfall was most concentrated or evident in these eight states does not mean the shortfall was limited to them. That would be unlikely since, altogether, they account for only 70 seats (16% of the House) and, depending on the projections used, the Republican shortfall may have been something on the order of 15 to 25 seats, maybe more. These eight states are more than the tip of the iceberg, but they are not the whole iceberg either.

Before moving on to explore what The 8 States might have had in common, other than their disproportionately large falls from Republican expectations, three implications of their distinctiveness should be noted. First, this finding adds to the many reasons for dismissing the common public opinion speculations for the Republican shortfall. What possible last-minute shift in public opinion strongly favoring Democrats was particularly strong in these eight states? Second, The 8 States finding also poses a problem for those dismissing the November surprise as catastrophically bad polling that had grossly overestimated how well Republican candidates were doing. If this were the case, why would the polls be fairly accurate in most of the country, but wildly wrong in just The 8 States and, in each of these eight, wrong in the same direction – greatly exaggerating Republican prospects? The third implication is that the evidence of the distinctiveness of these states suggests the Republican shortfall was not so much about votes in particular races, or even about voters in general, but about the politics of individual states.

The 8 States

We now have a good idea of where a disproportionate amount of the Republicans’ midterm shortfall took place. To get from “where” to “why” we need to wring more information out of this clue. We need to answer the “how” question. How did The 8 States differ from the other states? Other than being the sites of the most unexpectedly good Democratic outcomes in the midterm, what characteristics of these disparate states distinguish them from the rest of the nation? What could they possibly have in common with each other? Turns out, a great deal.

The 8 States differ a good bit from the other 42 states in five ways: their partisanship, their competitiveness in 2022 statewide races, their extensive use of mail-in voting, their level and party division of campaign spending, and their relative voter turnout rates. Table 6 presents many details of the evidence.

State Partisanship

The first measure of state partisanship is how the two presidential candidates fared in the 2020 election in the two groups of states (The 8 States and all other states). Overall in 2020, the 50 states divided down the middle between Donald Trump and Joe Biden, with 25 states going to Trump and 25 (plus Washington D.C.) to Biden. The 8 States along with their 88 electoral votes were swept by Biden. Eight wins, no losses. In the remaining 42 states, Biden carried only 17 (40%). Although these 17 included many states rich in electoral votes, The 8 States were critical to Biden’s victory.

A second partisanship indicator adds important perspective. Biden’s 2020 sweep of The 8 States does not mean they were safely in the Democrats’ camp. The tempering evidence of this is drawn from The Cook Political Report’s Partisan Voting Index (PVIsm). The PVI is a weighted average of a state’s deviation from the national vote in the previous two presidential elections. In a sense, it is like “the line” for a football game – which team is favored and by how much. In 2022, the PVI ranged from R+25 in the most Republican state of Wyoming to D+16 in the most Democratic state of Vermont. In about half the states (24), the index was in double digits one way or the other. None of The 8 States were in that category. The mean absolute PVI rating in The 8 States was 2.6 points, quite competitive. In the other 42 states, it is four times higher, 10.6 points.

Looking at the same data a bit differently, if we count states with a PVI of 2 points or less for either party as very competitive, six of The 8 States (75%) and only two of the other 42 states (5%, Maine and Minnesota) meet this very competitive standard. In short, The 8 States were very much up for grabs, but Democrats had managed to carry each of them in the most recent presidential election.

Intensity of Competition

As one might expect from states with a history of close partisan competition, every one of The 8 States had at least one major statewide hotly contested race in 2022. With the exception of the spotlighted gubernatorial contests in Michigan (Gretchen Whitmer vs. Tudor Dixon) and Arizona (Katie Hobbs vs. Kari Lake), Senate races dominated the stage. All seven Senate seats up for election (no Senate seat was up in Michigan) were high-profile, tight races. Five involved Democratic incumbents (Mark Kelly in Arizona, Michael Bennet in Colorado, Catherine Cortez Masto in Nevada, Maggie Hassan in New Hampshire, and Patty Murray in Washington); one a Republican incumbent (Ron Johnson in Wisconsin); and one open seat (the John Fetterman-Mehmet Oz race in Pennsylvania). Four of the seven governorships up (Washington was not electing a governor) could have gone either way (Arizona, Michigan, Nevada, and Wisconsin).

The intensely fought statewide battles taking place in each of The 8 States (usually involving Democratic incumbents) were not so common elsewhere. Only eight of the other 42 states (19%) had statewide races considered highly competitive (Georgia, Kansas, Maine, Minnesota, New Mexico, New York, Oklahoma, and Oregon).

Mail-In Voting

As a group, The 8 States also stand out from the others for their greater use of mail-in voting. Much of this evidence comes from the Fox News Voter Analysis of the AP-VoteCast survey conducted in the last week of the campaign by NORC. This study, an alternative to the traditional national Exit Poll, surveyed more than 92,000 voters nationally in 2022 with large state samples (often over 3,000 respondents) reported in 44 states, including each of The 8 States. The AP-VoteCast study asked respondents what mode of voting they used in casting their ballots – Election Day in-person, early voting in-person, or mail-in voting. The study reported 43% voted in-person on Election Day, 27% voted early in-person, and 31% voted by mail. The use of mail-in ballots varied a great deal from state to state.

In general, voting by mail was much more common in The 8 States than elsewhere (41% compared to 25%). Though mail-in voting was low in New Hampshire and below average in Wisconsin and Pennsylvania, it was quite high in the other five of The 8 States. Automatic mail-in ballot distribution to everyone on the registration rolls was also more common (three of the eight) than elsewhere (only five of the other 42). Whether in The 8 States or the rest of the country, Democrats typically beat Republicans by about 30 points in mail-in voting, typically about a 65-35 vote division. In several of The 8 States though, Democrats even bettered that. Pennsylvania stood out with a 56-point gap in its mail-in votes, a jaw-dropping 78-22 vote split, and Michigan (43 points, a 71.5-28.5 split) and Wisconsin (46 points, a 73-27 split) were not far behind.

Campaign Spending

An astronomical $2.5 billion was spent in the 35 Senate general election races of 2022, according to figures compiled by non-partisan Open Secrets (as of February 10, 2023). This was nearly $1 billion more than spent in the previous midterm and includes spending by both the major parties’ candidates as well as by outside groups supporting them. About half of 2022 Senate campaign spending (49%), over $1.2 billion, was spent in just the seven races of The 8 States. To repeat: half in the seven races of The 8 States and half in the other 28 races. Taking into account that the other 35 races include the very expensive Georgia runoff, the concentration of campaign spending in the seven contests is even more impressive.

Of the seven Senate races in The 8 States, six were among the 10 most expensive general election Senate campaigns (eight exceeded $140 million). The only Senate race in The 8 States not to make the Top 10 list was Colorado, and it was 11th. The average total spending (candidates and outside groups) in The 8 States’ races was nearly $173 million, about four times the average in the other 28 contests. Setting aside the unusual Georgia runoff Senate race, campaign spending in the average race among The 8 States was more than five times higher.

This extraordinary spending in the Senate campaigns of The 8 States disproportionately favored Democrats. Whether because of more big donors or better fundraising, Democrats had the money. In all but one of The 8 States’ races, the Democrat outspent the Republican (counting both candidate and outside group spending). Spending was nearly equal in the Washington contest. The median spending difference in The 8 States favored the Democrats by $21 million. The median race was in New Hampshire where over $59 million was spent for incumbent Democrat Maggie Hassan to “only” $38 million for her Republican challenger, Don Bolduc. But spending was even more lopsided in the Pennsylvania and Nevada races and reached its peak of a whopping $79 million disparity in the Arizona race between incumbent Democrat Mark Kelly and his Republican challenger Blake Masters.

This was nothing like the campaign finance world of the other 28 Senate races. The median spending difference in those states between the parties was, as these things now go, a paltry $3.7 million (vs. $21 million in The 8 States). And that favored the Republicans. Spending differences were under $10 million toward either party in about half (13) of these 28 races. (The most expensive and lopsided race of all, with a whopping $97.5 million difference in favor of the Democratic Party’s candidate, was Georgia, which fell just short of making The 8 States list.)

In short, a huge amount of money was poured into the midterm’s Senate campaigns; a wildly disproportionate amount into the seven Senate elections held in The 8 States; and a disproportionate amount of that was spent by and for the Democrats in those seven races – even though, as previously noted, those states were generally quite competitively balanced and one might have guessed that competitive balance would have carried over to campaign finance.

Turnout

The last distinguishing characteristic of The 8 States is that their turnout was high compared to the other states as well as to their own history in three prior midterms (2018, 2014, and 2010). The evidence is drawn from Michael McDonald’s US Elections Project. The state turnout rate used for 2022 is the Election Project’s “Preliminary Turnout Rate” reported in late January 2023 and the turnout rate of total ballots counted in the earlier midterms. This assessment of turnout uses each state’s turnout ranking, both compared to other states in the 2022 midterm and a comparison to its own ranking in the three previous midterms. To assess whether a state’s turnout is high, low, or somewhere in between requires a standard. The simple, though imperfect, standards used here are the comparative rankings of a state’s turnout within an election year (a static standard) and the change in its rankings among other states across previous elections (a dynamic standard).

Turnout in most of The 8 States was high compared to other states and to that of prior midterms. Six of the eight (75%) were in the Top 10 of turnout, and a majority (63%, five of eight) were ranked more highly than they had been in any of the previous three midterms. Even the three states that had been ranked more highly in a past midterm (Colorado, Washington, and Wisconsin) only failed the test because they had been ranked very highly in earlier midterms. In effect, they had been and remained near the top of the heap. For comparison, the other (non-8) states were far less likely to be among the highest rated turnout in 2022 (four of 42) and were less likely to have had stronger turnout ratings than in previous midterms (10 of 42).

The Breakwater Theory

From this body of evidence emerges The Breakwater Theory, a theory explaining what happened to November’s anticipated red wave. This evidence extends from specific polling undercutting popular speculations about the red wave’s collapse, to the stability of national conditions and public opinion from early in the campaign to Election Day, to the findings that the Republican shortfall was substantially concentrated in the re-labeled 8 Breakwater States and, finally, to the five politically important characteristics disproportionately shared by those states. The Breakwater Theory is the only theory consistent with all of this evidence regarding the Republican shortfall, having been essentially reverse-engineered from that evidence.

The Breakwater Theory contends that (1) national conditions and public opinion provided a strong basis for the development of a formidable red wave; (2) the red wave had formed with strong Republican prospects in both congressional and state elections; and (3) the expected red wave was not realized because Democrats constructed a breakwater preventing the full force of the red wave from hitting shore. The construction of the Democrats’ breakwater was the result of the confluence of the Democrats’ means, motives, and opportunities.

The Elements

Motives first and most obvious. The as yet unmentioned principal motive of Democrats in 2022 was the preservation of their tenuous Senate majority and, secondarily, the defense of threatened high-profile Democratic elected officials. Intense and pervasive political polarization in the public and in the parties elevated the stakes of both priorities.

The defense of every Senate Democrat’s seat was crucial in its own right, but also for what it meant to Senate control. Open seats and vulnerable Republican seats were high priorities as well, given the narrow margins and the probability that some Democratic incumbents would not survive. Preserving Democratic Senate control in the face of an impending red wave looked daunting, but under the circumstances and in light of midterm history, holding the House was not a real possibility. They had every reason to pull out all the stops in key Senate races.

Next comes opportunity. The prospect of Democrats fending off the red wave and holding control of the Senate was improved by several factors. Though the overall political climate favored Republicans, the political landscape of Senate elections favored Democrats. With control of the Senate going into the election, a status quo result amounted to a win. The class of Senate seats up in 2022 was also favorable. Democrats needed to defend only 14 of the 35 seats up, and eight of these 14 were safely in their column. All the remaining six seats represented by Democratic incumbents were in very competitive states (with Washington tilted to the Democrats) and each of them had been carried by Biden in 2020. The fact that three seats held by departing Republican incumbents were open seats (Pennsylvania, North Carolina, and Ohio) and another by a Republican regarded as vulnerable (Wisconsin) further opened up opportunities to the Democrats.

Finally, the means. Two factors combined to provide Democrats with the means to exploit these opportunities. The first was the prevalence of Democrat-friendly easy and early mail-in voting rules in the Breakwater States. The second was the enormous amount of financial support available to Democrats to fund extensive mobilization campaigns in these states – boosting the turnout of Democratic voters who likely would otherwise not vote. The already in-place candidate, party, and supporting organizations, important to earlier Democratic electoral success in these states, also likely contributed an important platform for mounting this mobilization effort.

Connecting the Dots

With the House virtually certain to go Republican and with Democrats having some advantages for holding their razor-thin control of the Senate, even in the face of national political winds strongly against them, the Democrats’ best bet was to go all-in on holding the Senate. Strategically, a small set of competitive states allowed them to focus their resources and offered, through early mail-in voting, performance-enhancing electoral rules conducive to well-organized mobilization campaigns that could raise the turnout of Democratic votes in those states. That is just what it did. The unlikely voters they mobilized undoubtedly had their own opinions about things, but in normal times and even in 2022 in other states without heavily financed mobilization campaigns, they and their opinions would have been inconsequentially on the sidelines. Mobilization made the difference and turned the election.

A mobilization campaign of this magnitude costs a great deal and Democrats had the money. The Democratic Party and its supporting outside groups and individuals spent in excess of $700 million on these seven races, over $200 million more than Republicans spent (then add another $250 million on the Democratic side for the Georgia race). The well-funded mobilization campaigns combined with the ease of mail-in balloting boosted Democratic turnout in these states. Once Democrats mobilized enough voters for their key Senate candidates, a significant number of Democratic House candidates down ballot, along with a few gubernatorial candidates, rode their coattails.

The final element of the Breakwater Theory concerns not what the Democrats did to construct their breakwater, but what Republicans failed to do to impede it. For Democrats to have blocked the red wave, they needed favorable election laws and rules and much more campaign spending than Republicans in the Breakwater States and a few more. If Republicans had been successful in restraining political machine-friendly mail-in voting rules and in matching the Democrats’ money offensive, they might have prevented the Democratic breakwater or, at least, reduced its effectiveness. But Republicans were nowhere near matching either Democratic money or organizational efforts in most of the eight Breakwater States.

Unlike all other proposed explanations, The Breakwater Theory not only fits all the evidence, but can be reconciled with the history and theories of midterm elections, midterm forecasting models, and the handicapping of midterm races by political analysts. Unlike the other explanations, it does not ask us to think that everything we knew about midterm elections based on many decades of observation, experience, and theorizing is, all of a sudden, wrong – up in smoke, as if electoral history had expired. There were sound reasons to have anticipated a red wave – it had developed (as the consensus of late polls and projections attests), and then an unprecedented confluence of unusual conditions blocked it from being realized.

As Columbo Would Say, “One More Thing”

The Breakwater Theory provides a coherent evidence-based explanation of what happened to the red wave, but it still leaves one troubling loose end. Assuming the theory is right, that well-heeled Democrats in mobilization-friendly, heavy mail-in voting, politically competitive states with crucial statewide races on the line pulled out all the stops to raise turnout for Democratic candidates and push them over the top, why weren’t these mobilized votes reflected in the pre-election polls in those states? Why wasn’t the Republican shortfall of results from expectations already factored into lowered expectations? If anything, rather than downgrading Republican prospects, Republican prospects improved somewhat in the closing weeks of the campaign. When the votes were finally counted, Democrats in each of the 14 statewide races in the 8 Breakwater States outperformed their polls, often by wide margins. Why?

The theory’s focus on voter mobilization in explaining the November surprise makes this question all the more puzzling. Voter mobilization efforts, especially of this magnitude and especially with so much early-voting and such very early early-voting (often beginning in September) would have both taken a great deal of time to execute and had plenty of time to be reflected in the many state polls. How did these mobilized voters, casting their ballots over a significant stretch of time, fly under the radar of so many pollsters in every one of the Breakwater States?

On this, I do not have evidence, but I have a suspicion. All the polls reported in these states and informing those making election ratings were surveys of likely voters. Polls of likely voters are now standard. The problem is that the Democratic mobilization campaigns were most interested in adding votes to the Democratic columns, rounding up votes from those unlikely to otherwise vote. The polls, on the other hand, are most interested in and most likely to include likely voters – not unlikely voters. Unlikely voters, normally non-voters, are notoriously difficult to get into survey samples. Their interest in politics is often marginal, steering them away from pollsters as well as from voting.

This problem is nothing new to survey research. It goes back at least to The American Voter, the classic 1960 study of voting behavior, and is one reason why turnout rates in surveys are always higher than they are in reality. So, these polls of likely voters may have under-reported the Democratic vote in the 8 Breakwater States partly because many of these unlikely voters who voted never made it into survey samples to begin with or were weeded out of reports of the intended vote because they were not regarded as likely to vote.

Interpretations

As late as Election Day, the 2022 midterm appeared headed for a clear verdict with an obvious explanation. Had the election run its normal course, it would have been easily interpreted as a referendum on the in-party, reflecting dissatisfaction with the in-party’s record and generating a red wave. But the Democratic breakwater intervened, leaving behind the November surprise, pleasing Democrats and disappointing Republicans. The diversion of the red wave complicated matters in many ways. Though the impact of the midterm’s diversion was felt nationally, it was greatly concentrated in a group of states. Though its effects were most conspicuous in House results, it had been driven mostly by Senate races. This midterm was not typical and certainly not easily interpreted. So how should the midterm’s outcome with its surprise ending be properly interpreted?

Some see the midterm’s jolting outcome as a triumph of democracy, the public’s repudiation of Republicans and vindication of Democrats. The fact that Democrats fared much better than expected is taken as evidence for this conclusion. The Breakwater Theory, however, says otherwise. Democrats did not do relatively well because they convinced skeptical voters late in the campaign that they had governed successfully through the first half of President Biden’s term, or because the midterm had morphed into a “choice” election. There was no epiphany.

There is no need to revisit the abundant polling evidence that a large majority of Americans were not at all pleased with the performance of Biden-led Democrats. Americans were not closely divided about this and that was reflected in the anticipated red wave. Poll after poll, of registered voters or all adults in the Exit Poll or the AP-VoteCast Poll, all set Biden’s approval rating in the low 40s throughout the campaign to Election Day. No presidential party this badly viewed by the public had escaped its midterm with anywhere near such a weak slap on the wrist. Apart from 2014 when the out-party hit its historic high number of seats, every president since 1946 whose midterm Gallup approval was 45% or less on Election Day lost at least 26 seats (a mean of 42 seats). President Biden’s Gallup rating was only 40%, yet Democrats lost only nine seats, about a third of the previous low for an unpopular president. A truly small-d democratic outcome in this midterm, one reflecting the will of the people, would have been far more severe – some level of a red wave.

The last-minute nosedive of Republican fortunes was not about a change in the grand fundamentals of democratic elections. It was not about national conditions or issues, or about candidate quality or internal party divisions, and not about either Biden or Trump. The expectations of a Republican wave reflected public opinion, but their surprising fall from those expectations was not about public opinion at all. It was about the campaign system – the combined elements of mobilization-friendly and early mail-in balloting, large campaign organizations to gather the votes, and an enormous amount of money, all coming together for one party focused on a number of politically important races in competitive states. In many ways, it might be characterized as a 21st century incarnation of the machine politics of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Republicans in 2022 were caught flat-footed in securing reasonable limits to easy/early mail-in voting and were badly outspent by Democrats who used the rules and their resources for rounding up enough votes in the right places to block the red wave. As George Washington Plunkitt, a late 19th century leader of the legendary Tammany Hall political machine, might have said about those running the 21st century version of political machines: “They seen their opportunities and they took ’em.”

James E. Campbell is a UB Distinguished Professor of Political Science at the University at Buffalo, SUNY. He is author of “The Presidential Pulse of Congressional Elections” (University Press of Kentucky, 1993 and 1997), and his most recent book, “Polarized: Making Sense of a Divided America” (Princeton, 2016 and 2018), was a Choice Outstanding Academic Title.

https://ift.tt/vcZtk5O

from ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/vcZtk5O

via IFTTT

0 comments

Post a Comment