Emerging Market Vulnerability Heatmap: Are EMs Threatened By Increasing Inflation Expectations

By Wouter van Eijkelenburg, economist at Rabobank

Emerging Market Vulnerability Heatmap

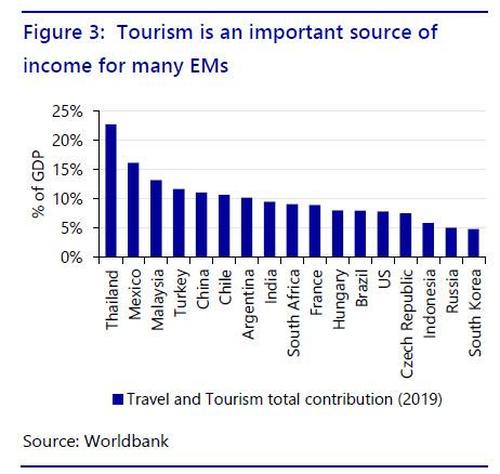

Summary

- There are divergent paths to economic recovery in advanced economies and emerging markets, due in part to differences in Covid-19 infections and vaccination rates

- Inflation expectations are increasing in advanced economies, raising questions on central bank policies going forward

- Tapering of QE or even policy interest rates hikes by central banks in advanced economies, particularly by the Fed, pose downside risks to the economies of emerging markets

- Our vulnerability Heatmap provides an overview of economic indicators that signal potential vulnerabilities for certain emerging markets

- Factors like a country’s (foreign currency denominated) debt, international trade position and interest rate risks are important determinants for EM vulnerability

- We examine these factors in detail for certain emerging markets by diving into debt metrics, current accounts and interest rates

Back to business?

In 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic triggered the largest crisis since WW2. Across the world countries went into lockdown to mitigate the spread of the corona virus. While they succeeded in containing the virus, the lockdowns had severe economic implications. Governments and central banks have stepped in by providing enormous amounts of fiscal and monetary stimulus in order to counter the negative economic consequences of the imposed lockdowns. A recent publication showed that economic contractions could have been much worse if there had been no additional fiscal stimulus by governments.

Halfway through 2021, we are seeing restrictions being loosened in many parts of the world due to increased vaccination rates. Although the virus is far from beaten, as new variants continue to emerge, economies are opening up globally and the economic outlook for most, if not all, countries is improving. A better economic outlook might require other policies by central banks and governments as inflationary pressure intensifies. However, economies are not all recovering at the same pace, and every economy has its own individual characteristics and autonomous regime. In this publication we will explore some of the implications of divergent economic growth paths between advanced economies (AEs) and emerging markets (EMs) with a special focus on the vulnerability of emerging markets to potential tighter monetary policy by AEs.

Different speeds of recovery

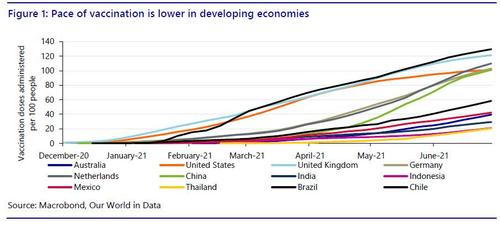

Globally, all of us have felt the impacts of the pandemic. But the intensity, limitations and consequences vary per country and probably even per person. Diverse policy actions have led to differences between countries in terms of virus penetration, containment success and economic consequences. Furthermore, we have seen that AEs have a greater vaccine availability and better logistical networks to start vaccinating quickly and effectively while most EMs are lagging behind. Figure 1 shows the varied pace of vaccination rates, which tends to be lower for most EMs (notwithstanding some exceptions, like Chile). It’s generally thought that higher vaccination rates allow economies to open up with a reduced risk of infections rising and therefore a lower risk of new waves of the virus hitting the country and economy.

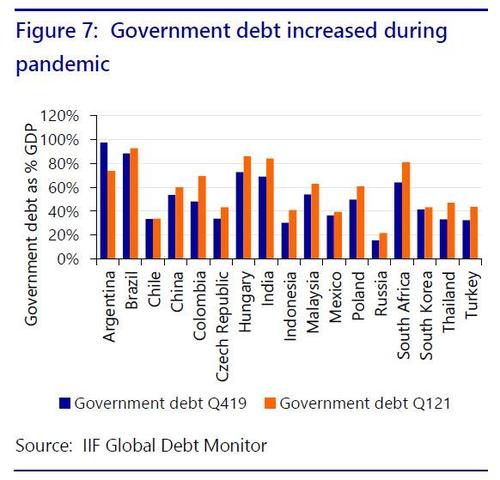

While many Europeans are planning or enjoying summer holidays at home abroad, countries like Indonesia, Thailand and Vietnam are close to or at the highest number of infections since the start of the pandemic. At the same time, India is still licking its wounds after a devastating 2nd wave, while other countries like Brazil, Argentina, and Colombia still need to up their games and improve their current pace of vaccination. These differences translate into the path to economic recovery and the economic outlook going forward. Figure 2 shows GDP growth per country compared to what it would have been in the absence of the Covid-19 pandemic based on average GDP growth in the period 2011-2019. Figure 2 illustrates that not only did AEs (solid lines) generally suffer less than EMs (dashed lines) in terms of “lost” growth in 2020, they are also better able to regain lost ground in 2021 through to 2022. The US is expected to have regained almost all lost ground by the end of 2022. In contrast by the end of 2022 especially Asian EMs like Thailand, India and Indonesia will still face a loss of almost 10% in economic output due to the crisis.

Structural impact on the economy

Manufacturing in general bounced back relatively quickly in 2021 (especially compared to the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis), due to pent-up demand, government support to households in advanced countries and more spending in durables instead of services. The car industry has been the largest driver of the manufacturing recovery, accounting for about 35 percent of the global rebound in the second half of 2020, while electrical equipment accounted for almost 5 percent of the rebound.

However, the economic recovery is mainly driven by large, while small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) were hit very hard by the pandemic, due to lower capital levels, lower capacity to adjust to remote working, and lower access to government funds. Moreover, the penetration of online retailers increased substantially during the lockdowns, which reduced the market share of traditional SMEs. In most emerging markets, the line between the SMEs and the informal sector is quite blurred, making it particularly difficult for these companies to receive government support. Support for SMEs was an important part of government packages in many countries: the Brazilian government dedicated 58.0% of their BRL1.27trn package to support workers and firms, the Indian government extended guarantees for SME loans, created a fund for equity infusion and loosened the regulations; Turkey offered an extended lending scheme for SMEs ; Thailand approved close to USD 20bn in soft loans to SMEs (both through private banks and directly from the government), to name but a few. It is likely that in the coming years non-payment of these loans or guarantees might materialize as liabilities for the sovereigns states.

Rising inflation (expectations)

The recovering economic growth and optimistic growth outlook in AEs increase pressure on prices in a number of ways, potentially leading to higher inflation. This extensive report dives deeper into drivers for inflation and potential scenarios. Here we give only a brief description of some main drivers of current inflation expectations: Firstly, the restrictions of the pandemic are fading, leading to higher private consumption and consumer confidence which increases demand and puts pressure on prices. Secondly, global commodities prices are surging (Figure 4) which increases input costs for manufacturers and potentially pushes costs down the supply chain, leading to higher prices. Thirdly, most central banks have an ultra-accommodative stance: this means low interest rates and low borrowing costs, leading to increased investments and potentially an increase in prices (for example, housing prices). Finally, fiscal stimulus by governments is very large (as explained in this publication), which also has the potential to increase inflation.

Reaction of central banks

All of these factors push up inflation expectations. Recently, we have already seen the first examples in the US and UK, where inflation figures were higher than expected. Many central banks explain the rise in inflation as “transitory”, but the voices questioning the length of the period of higher inflation are getting louder. These developments cause us to wonder: what are central banks going to do? The question is particularly relevant for the Fed, as any material policy decisions related to inflation, which accelerated again in June, and a more hawkish stance by the Fed will potentially have direct consequences for the financial stability of EMs.

The last time the Fed started tapering had dramatic consequences for many EMs, known as the “taper tantrum” back in 2013. One of the main reasons for the sudden collapse of EM currencies was that the tapering came somewhat unexpectedly. Therefore the Fed tries to be as predictable as possible in order to prevent such shocks going forward. For this reason, Fed chair Powell speaks about an advanced notice, which will signal any changes in policy before announcing a decision on a change in asset purchases. So how far away are we from an advanced notice?

As we explain in our comments on the FOMC, the minutes from June highlight that the rise in inflation was higher than anticipated and a substantial majority of the participants think inflation risk is towards the upside. Furthermore, various participants expect the conditions to start reducing the pace of asset purchases (tapering) somewhat earlier than they expected previously. The median FOMC participant now expects two rate hikes of 25bps in 2023 instead of zero last March. Meanwhile, the discussion on tapering has started and Powell’s advance notice could come as soon as the Jackson Hole symposium in late August or the FOMC meeting in September.

How vulnerable are EMs to any tightening of monetary policy at this time? Especially taking into account the asymmetry in the pandemic and divergence in economic recovery as described above.

Risks for emerging markets

Explosive cocktail in the making

Tightening monetary policy in the US generally pushes up US yields and may also strengthen the USD verses EM currencies. This can potentially reverse some of the international capital flows which have been flowing towards EMs in the past year as a spill-over effect of the ultra-loose fiscal and monetary policy by advanced economies (Figure 5). These spill-over effects strengthened emerging market currencies over the last year, pushing them close to the highest level in a decade (Figure 6). The strength of the EM currencies, as a result of the capital inflows, helped EM governments in providing affordable financing to battle the consequences of the pandemic. However, there may be an explosive cocktail in store for vulnerable EMs due to the combination of weakening of domestic currencies vs. USD as a result of FED policy action, increased foreign currency debt levels as a result of Covid-19, high commodity prices (including oil), and faltering domestic recovery as a result of new waves of Covid-19.

The ‘EM Vulnerability Heatmap’ as presented in Table 1 provides an overview of many economic indicators which allow us to asses and compare the relative vulnerability of EMs. In the next section we dive deeper into five indicators that could be valuable in order to assess a country’s vulnerability.

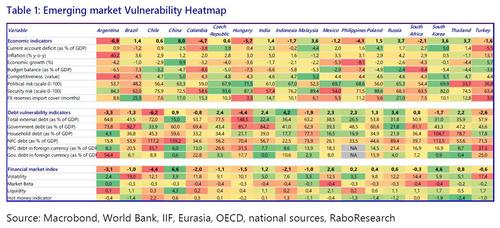

Public debt levels have increased across the board

Governments have increased expenditures as a reaction to the negative economic consequences of the pandemic, resulting in higher debt levels (as a % of GDP) in many countries (Figure 7). Especially Colombia, India and South Africa show large increases in public debt over the past year.

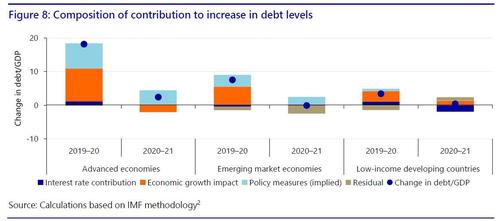

However, by using a methodology developed by Mauro and Zilinsky (Figure 8) we are able to nuance the growth in public debt to GDP ratio. Interestingly, despite falling interest rates, the interest expenses of advanced economies have slightly increased due to massive increases in the gross debt level. Simultaneously, we observe that the interest expense in emerging economies is only a marginal effect of the increase in public debt, while the loss in economic growth accounts for a much more significant part of the increase in public debt to GDP ratio. What is even more striking is that economic growth had a greater impact on the increase in debt to GDP ratio than fiscal policy measures in EMs. Figure 8 demonstrates that economic growth plays a much bigger role in emerging markets and low-income developing economies. In other words, economic growth rates are very important with regard to managing sustainable public debt levels. As already mentioned above, this is precisely what might work against EMs in 2021 as long as vaccination programs are slow to develop and the spread of the virus continues to drag on the economy.

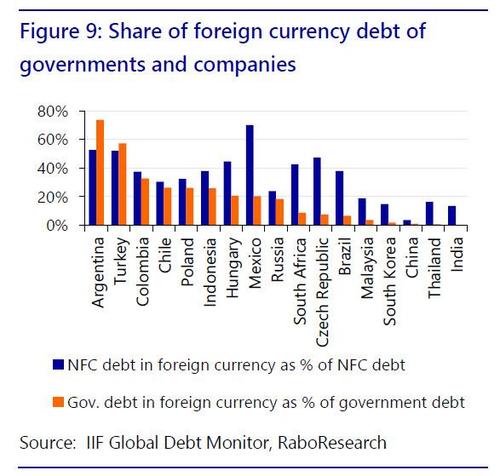

Nonetheless, while total public debt levels provide valuable information on the fiscal state of a country, there are other metrics which are well suited to explain EMs’ vulnerability. Debt levels are not always directly affected by any of the exogenous factors we discussed above (like increasing US interest rates). Therefore, a better indicator to gauge vulnerability would be the part of the total debt which is denominated in a foreign currency. : If the USD (or other foreign currency) were to strengthen versus the domestic currency this could have severe implications for the sustainability of EM debt levels Why? As the domestic currency depreciates this essentially increases the debt level in domestic currency. This implies that the higher your foreign currency denominated debt level is, the more vulnerable your fiscal position with regard to a depreciating currency.

Moreover, a country can only service its foreign currency debt by reducing its currency reserves and/or earning enough currency in foreign trade. So apart from holding external FX reserves and international assets, a positive current account balance is crucial for these countries. On the other hand, a deficit here increases their financial troubles. We will look at the current account in more detail in the next section. Figure 9 shows that the governments of countries on the left-hand side like Argentina, Turkey and Colombia are relatively vulnerable in terms of foreign currency debt. China, Thailand and India have less foreign currency debt , making them less vulnerable to exogenous shocks that affect the price of the domestic currency.

Trade positions have shifted due to the pandemic

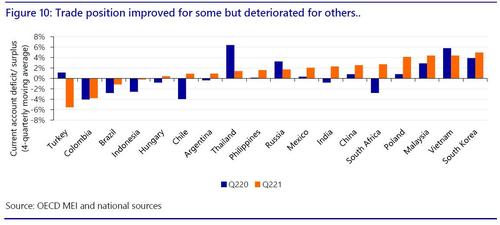

The pandemic hit countries in an asymmetric fashion as a result of diverse characteristics of domestic economies. This has also undoubtedly been the case with regard to trade. There have been swings in the current account of many emerging countries, in a positive sense for some and negative for others. A few developments that were aa direct consequence of the pandemic impacted the current account over the course of last year. Firstly, increased demand for medical goods meant that exporters of health-related products or inputs saw a dramatic rise in demand for their products. Secondly, at the same time, due to lockdowns in advanced economies people were unable to spend their money on services and therefore private expenditures shifted partly towards purchasing goods. This higher demand for goods from AE’s increased exports of products for emerging markets that produce these goods. Thirdly, over the course of the year commodity prices started to increase (Figure 4): this was due to a more positive economic growth outlook that increased demand and benefitted commodity exporters but negatively impacted commodity importers. Finally, domestic import of products and services collapsed in many EMs as a result of lower domestic consumption during the crisis, thereby increasing the current account. Figure 10 illustrates and compares the differences in current accounts of EMs from Q2 2020 to Q2 2021.

The recent developments pose certain risks to the current account going forward. Firstly, as the coronavirus slowly fades, consumers in AEs might substitute the expenditures on goods back to services, which decreases the exports of EMs over time, shifting back to pre-corona levels. The second is that the de-globalisation trend will continue going forward and re-shoring will move some export products from EMs towards AEs. As explained earlier, a current account surplus makes it easier for countries to service their foreign currency debt. However, if one of the above scenarios materializes this might negatively impact the current account, leaving some EMs with current account deficits. In such a scenario the export cover is a factor that could limit the domestic FX currency risks. In Figure 11 we show how many months of imports can be covered by the FX reserves of the country. We observe that countries on the left-hand side, like Brazil, Russia and China, have many FX reserves, mitigating the risks of a depreciating currency. In contrast countries like Mexico, Hungary and Turkey are more vulnerable to FX shocks.

Interest rate costs

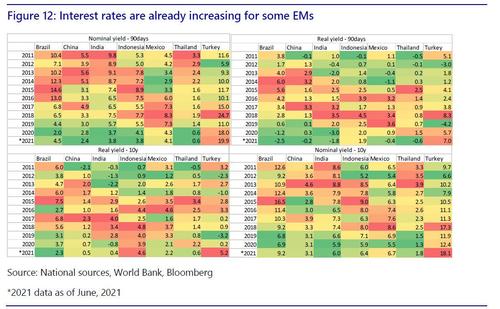

Nominal and real rates of EMs have steadily decreased over the past year partly as a result of the pandemic. But it is likely that 2021/22 will see a rise in interest rates across the emerging markets. This can be clearly seen with Brazil which is poised to hike its Selic rate by year-end to levels seen before the pandemic, but it has also been the case for other EMs like Russia and Chile. Anticipation of a US normalization of monetary policy might add pressures for central banks to hike sooner across the board.

To give a more nuanced picture we have captured the real short-term interest rates (ex-post) in Figure 12. These are negative for five out of the seven countries in consideration (nominal rate adjusted for inflation) in 2021. Countries are using this as an opportunity to increase short-term borrowing instead of longer-term borrowing. This has been observed across both AEs and EMs. The strategy is to roll over short-term debts in the current “higher” inflation environment and wait for the market uncertainty to settle before converting it to long-term debt. Some countries like China and Mexico are relying on recovering revenues to pay back this debt, while others, like India, are also looking at privatization of public sector entities for the required cash.

However, emerging markets will probably not be benefitting from negative real interest rates forever. Figure 12 already illustrates that nominal and real interest rates have started to climb in some countries over the course of 2021. So while the public debt figures kept climbing, the pandemic (or rather the related fiscal and monetary measures) temporarily reduced the cost of financing for most countries. Nevertheless, there is an increasing likelihood of higher interest rates on the back of inflation expectations and subsequent rate hikes by central banks. Higher interest rates will probably lead to higher interest rate costs for EMs, posing a threat to debt sustainability going forward.

Having discussed some important indicators to monitor with regard to emerging market vulnerability, the question is: how do all of these factors add up?

The final ranking

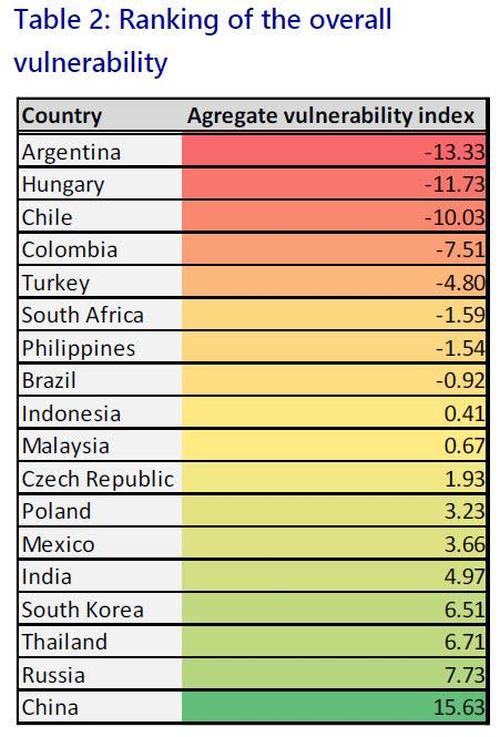

Table 1 summarizes the main factors determining EM vulnerability according to the indicators included in our Heatmap. In Table 2 we have added them up to get a general sense of which countries can be deemed more vulnerable with regard to the indicators included. In general we see that LatAm countries are relatively vulnerable compared to their peers. Asian countries are relatively less vulnerable, although the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia are increasingly vulnerable and rank lower compared to six months ago. The same holds for South Korea, although it is still close to the top of the chart. European countries are now better ranked than 6 months ago although their individual scores did not improve so much.

In conclusion, we hope that the use of the Heatmap and accompanying economic indicators has helped to sketch a clear picture of potential risks and vulnerabilities of EMs. Naturally, they help to indicate risks and compare the relative vulnerabilities of EMs. However, keep in mind that these are based on current economic indicators and are therefore an illustration of the current situation and vulnerability. They do not include any forecasts or have the intention to rank future economic performance of the countries included.

https://ift.tt/3iJR2p3

from ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/3iJR2p3

via IFTTT

0 comments

Post a Comment