The 'Great Game' Moves On

Authored by Alasdair Macleod via GoldMoney.com,

Following America’s withdrawal from Afghanistan, her focus has switched to the Pacific with the establishment of a joint Australian and UK naval partnership.

The founder of modern geopolitical theory, Halford Mackinder, had something to say about this in his last paper, written for the Council on Foreign Relations in 1943. Mackinder anticipated this development, though the actors and their roles at that time were different. In particular, he foresaw the economic emergence of China and India and the importance of the Pacific region.

This article discusses the current situation in Mackinder’s context, taking in the consequences of green energy, the importance of trade in the Pacific region, and China’s current deflationary strategy relative to that of declining western powers aggressively pursuing asset inflation.

There is little doubt that the world is rebalancing as Mackinder described nearly eighty years ago. To appreciate it we must look beyond the West’s current economic and monetary difficulties and the loss of its hegemony over Asia, and particularly note the improving conditions of the Asia’s most populous nations.

Introduction

Following NATO’s defeat in the heart of Asia, and with Afghanistan now under the Taliban’s rule, the Chinese/Russian axis now controls the Asian continental mass. Asian nations not directly related to its joint hegemony (not being members, associates, or dialog partners of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation) are increasingly dependent upon it for trade and technology. Sub-Saharan Africa is in its sphere of influence. The reality for America is that the total population in or associated with the SCO is 57% of the world population. And America’s grip on its European allies is slipping.

NATO itself has become less relevant, with Turkey drawn towards the rival Asian axis, and its EU members are compromised through trading and energy links with Russia and China. Furthermore, France is pushing the EU towards establishing its own army independent of US-led NATO — quite what its role will be, other than political puffery for France is a mystery.

It is against this background that three of the Five Eyes intelligence partnership have formed AUKUS – standing for Australia, UK, and US — and its first agreement is to give Australia a nuclear submarine capability to strengthen the partnership’s naval power in the Pacific. Other capabilities, chiefly aimed at containing the Chinese threat to Taiwan and other allies in the Pacific Ocean, will surely emerge in due course. The other two Five Eyes, Canada and New Zealand, appear to be less keen to confront China. But perhaps they will also have less obvious roles in due course beyond pure intelligence gathering.

The US, under President Trump, had failed to contain China’s increasing economic dominance and its rapidly developing technological challenge to American supremacy. Trump’s one success was to peel off the UK from its Cameron/Osbourne policy of strengthening trade and financial ties with China by threatening the UK’s important role in its intelligence partnership with the US.

For the UK, the challenge came at a critical time. Brexit had happened, and the UK needed global partners for its future trade and geopolitical strategies, the latter needed to cement its re-emergence onto the world stage following Brexit. Trump held out the carrot of a fast-tracked US/UK trade deal. The Swiss alternative of neutrality in international affairs is not in the UK’s DNA, so realistically the decision was a no-brainer: the UK had to recommit itself entirely to the Anglo-Saxon Five-Eyes partnership with the US, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand and turn its back on China.

But gathering intelligence and building naval power in the Pacific won’t defeat the Chinese. All simulations show that the US, with or without AUKUS, cannot win a military conflict against China. But AUKUS is not a formal model on NATO lines which commits its members by treaty to aggression against a common enemy. While Taiwan remains a specific problem, the objective is almost certainly to discourage China from territorial expansion and protect and give other Pacific nations on the Asian periphery the security to be independent from the SCO behemoth. The trade benefits of closer relationships with these independent nations are also an additional reason for the UK to join the CPTPP — the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership. It qualifies for membership through its sovereignty over the Pitcairn Islands. And that is why China has also applied to join.

Therefore, AUKUS’s importance is in the signal sent to China and the whole Pacific region, following the abandonment of land-based operations in the Middle East and Afghanistan. The maritime threat to China is a line which must not be crossed. We are entering a new era in the Great Game, where the objective has changed from dominance to containment. Having lost its position of ultimate control in the Eurasian land mass America has selected its partners to retain control over the high seas. And the UK has found a new geopolitical purpose, re-establishing a global role now that it is independent from the EU.

The French cannot join the CPTPP being bound into the common trade policies of the EU. Seeing the British escape the strictures of the EU and rapidly obtain more global influence than France could dream of has touched a raw nerve.

Mackinder vindicated

The father of geopolitics, Halford Mackinder, is frequently quoted and his theories are still relevant to the current situation. Much has been written about Mackinder’s prophecies. His concept of the World Island was first mentioned in his 1904 presentation to the Royal Geographic Society in London: “a pivot state, resulting in its expansion over the marginal lands of Euro-Asia”.

In 1943 he updated his views in an article for the Council on Foreign Relations, adding to his heartland theory. Written during the Second World War, his commentary reflected the combatants and their positions at that time. But despite this, he made a perceptive comment relative to the situation today and AUKUS:

“Were the Chinese for instance organised by the Japanese to overthrow the Russian Empire and conquer its territory they might constitute the yellow peril to the world’s freedom just because they would add an oceanic frontage to the resources of the great continent.”

When Mackinder wrote his article the Japanese had already invaded Manchuria, but their subsequent defeat removed them from an active geopolitical role, and in place of a Soviet defeat China has entered a peaceful partnership with Russia that extends to all its old Central Asian soviet satellites. It is the focus on the ocean frontage that matters, upon which the maritime silk road depends.

The article brings into play another aspect mentioned by Mackinder, and that is the Heartland’s tremendous natural resources, “…including enough coal in the Kuznetsk and Krasnoyarsk basins capable of supplying the requirements of the whole world for 300 years”. And:

“In 1938 Russia produced more of the following food stuffs than any other country in the world: wheat, barley, oats, rye, and sugar beets. More manganese was produced in Russia than in any other country. It was bracketed with United States in the first place as regards iron and it stood second place in production of petroleum”.

Through its partnership with Russia all these latent resources are available to the Chinese and Russian partnership. And the real potential for industrialisation, held back by communism and now by Russian corruption, has barely commenced.

After presciently noting that one day the Sahara may become the trap for capturing direct power from the sun (foreseeing solar panels), Mackinder’s article ended on an optimistic note:

“A thousand million people of ancient oriental civilisation inhabit the monsoon lands of India and China [today 3 billion, including Pakistan]. They must grow to prosperity in the same years in which Germany and Japan are being tamed to civilisation. They will then balance that other thousand million who live between the Missouri and the Yenisei [i.e., Central and Eastern America, Britain, Europe and Russia beyond the Urals]. A balanced globe of human beings and happy because balanced and thus free.”

Both China and now India are rapidly industrialising, becoming part of a balanced globe of humanity. While the West tries to hang on to what it has got rather than progressing, China and India along with all of under-developed Asia are moving rapidly in the direction of individual freedom of economic choice and improvements in living conditions, to which Mackinder was referring.

Obviously, there is some way for this process yet to go, displacing western hegemony in the process. America particularly has found the political challenges of change difficult, with its deep state unable to come to terms easily with the implications for its military and economic power. We must hope that Mackinder was right, and the shift of economic power is best to be regarded as the pains of geopolitical evolution rather than conditions for escalating conflict.

But in pursuing its green agenda and eschewing carbon fuels, the West is unwittingly handing a gift to Mackinder’s Heartland, because despite diplomatic noises to the contrary China, India and all the SCO membership will continue to use cheap coal, gas, and oil which Asia has in abundance while Western manufacturers are forced by their governments to use expensive and less reliable green energy.

Green obsessions and global trade

Meanwhile, the West has gone green-crazy. Banning fossil fuels without there being adequate replacements must be a new definition of insanity, for which the current fuel crises in Europe attest. With over 95% of European logistics currently being shifted by diesel power, switching to battery power or hydrogen by 2030 by banning sales of new internal combustion engine vehicles is a hostage to fortune.

While it is hardly mentioned, presumably the Western powers think that by banning carbon fuels they will take the wind out of Russia’s energy quasi-monopoly, because including gas Russia is the largest exporter of fossil fuels in the world. Instead, the West is creating an energy shortage for itself, a point driven home by Gazprom withholding gas flows through its pipelines to Europe, thereby driving up Europe’s energy costs sharply and ensuring a far more severe energy crisis this winter.

Even if Russia turns on the taps tomorrow, there is insufficient gas storage in reserve for the winter months. And Europe and the UK have got ahead of themselves by decommissioning coal and gas-fired electricity. In the UK, a massive undersea gas storage facility off the Yorkshire coast has been closed, leaving precious little national storage capacity. As we have seen with the post-covid supply chain chaos, energy problems will not only become acute this winter, but are likely to persist through much of next year. And even that assumes Russia relents and moderates its energy stance to European customers.

By way of contrast, though its partnership with Russia China is gifted unlimited access to all carbon fuels. She is still building coal-fired electricity power stations at an extraordinary rate — according to a BBC report there are 61 new ones being commissioned. A further 51 outside China are planned. As a sop to the West China has only said she won’t finance any more outside her territory. And India relies on coal for over two-thirds of its electrical energy. While Europe and America through their green obsessions are denying themselves the availability and technologies that go with carbon fuels, the Russian/Chinese axis will continue to reap the full benefits.

The West’s response is likely to be to decry Chinese pollution and its contribution to global warming, but realistically there is little it can do. Demand for Chinese-manufactured goods will continue because China now has a quasi-monopoly on global manufacturing for export. In the unlikely event western consumers become avid savers while their governments continue to run massive budget deficits, their trade deficits will rise even more, allowing Chinese exporters to increase prices for consumers and intermediate goods without losing export sales.

While there is nothing it can do about China’s production methods, AUKUS members will undoubtedly lean on other exporting CPTPP members to comply with global green policies. But they will be competing with China, and while they may pay lip service to the climate change agenda, in practice they are unlikely to implement it without holding out for unrealistic subsidies from the western nations driving the climate change agenda.

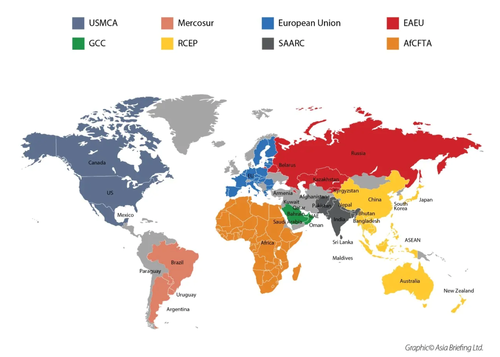

Under current circumstances, it seems unlikely that China’s CPTPP application will lead to membership, given the CPTPP requirement for China’s central government to relinquish ownership of its SOEs and to permit the free flow of data across its borders. In any event, China is focused on developing its Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a free trade agreement with ratification signed so far by China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand. It will come into effect when ratified by ten out of the fifteen signatories, likely to be in the first half of 2022, and in terms of population will be two and a half times the size of the EU and the US/Mexico/Canada (USMCA) trade agreements combined.

With four out of five of the signatories being American allies, RCEP demonstrates that the AUKUS defence partnership is an entirely separate issue from trade. While the US may not like it, if RCEP goes ahead freer trade will almost certainly undermine a belligerent stance in due course. Despite hiccups, the progression of trade dealing in the Pacific region promises to prove Mackinder right about the prospect of a more balanced world. All being well and guaranteed by a balance of naval capabilities between AUKUS and China, a free-trading Pacific region will render the European and American trade protectionist policies an anachronism. But the threat is now from another direction: financial instability, with western nations pulling in one direction and China in another.

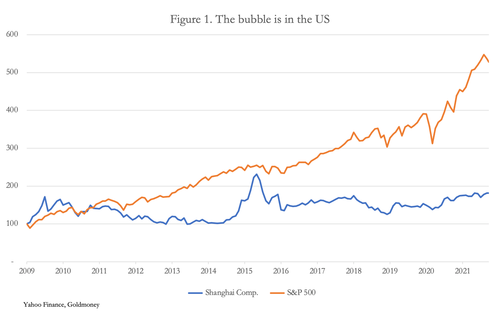

Since the Lehman collapse and the ensuing financial crisis, China has been careful to prevent financial bubbles. Figure 1 shows that the Shanghai Composite Index has risen 82% since 2008, while the S&P500 rose 430%. While the US has seen financial asset values driven by a combination of QE and investor speculation, these factors are absent and discouraged in China. Government debt to GDP is about half that of the US. It is true that industrial debt is high, like that of the US. But the difference is that in China debt is more productive while in America there has been a growing preponderance of debt zombies, only kept solvent by zero interest rate policies.

China’s policy of ensuring that the expansion of bank credit is invested in production and not speculation differs fundamentally from the US approach, which is to deliberately inflate financial assets to perpetuate a wealth effect. China avoids the destabilising potential of speculative flows unwinding because it lays the economy open to the possibility that America will use financial instability to undermine China’s economy.

In a speech to the Chinese Communist Party’s Central Committee in April 2015, Major-General Qiao Liang, the People’s Liberation Army strategist, identified a cycle of dollar weakness against other currencies followed by strength, which first inflated debt in foreign countries and then bankrupted them. Qiao argued it was a deliberate American policy and would be used against China. In his words, it was time for America to “harvest” China.

Drawing on Chinese intelligence reports, in early 2014 he was made aware of American involvement in the “Occupy Central” movement in Hong Kong. After several delays, the Fed announced the end of QE the following September which drove the dollar higher, and “Occupy Central” protests broke out the following month.

To Qiao the two events were connected. By undermining the dollar/yuan rate and provoking riots, the Americans had tried to crash China’s economy. Within six months the Shanghai stock market began to collapse with the SSE Composite Index falling from 5,160 to 3,050 between June and September 2015.

One cannot know for certain if Qiao’s analysis was correct, but one can understand the Chinese leadership’s continued caution based upon it. For this and other reasons, the Chinese leadership is extremely wary of having dollar liabilities and the accumulation of unproductive, speculative money in the economy. It justifies their strict exchange control regime, whereby dollars are not permitted to circulate in China, and all inward capital flows are turned into yuan by the PBOC.

Furthermore, domestic monetary policy appears deliberately different from that of America and other western nations. While everyone else has been inflating their way through covid, China has been restricting domestic credit expansion and curtailing shadow banking. The discount rate is held up at 2.9% with market rates slightly lower at 2.2%, and the only reason it is that low is because alternative dollar rates are at zero and EU and Japanese rates are negative.

It is this restrictive monetary policy that has led to the current crisis in property developers, with the very public difficulties of Evergrande. Far from being a surprise event, with cautious monetary policies it could have been easily foreseen. Moreover, the government has a sensible policy of not rescuing private sector businesses in trouble, though it is likely to take steps to limit financial contagion.

In their glass houses, Western critics continually throw stones at China. But at least her policy makers have attempted to avoid contributing to the global inflation cycle. With prices beginning to rise at an accelerating pace in western currencies, a new global financial crash is in the making. China and her SCO cohort would be adversely affected, but not to the same extent.

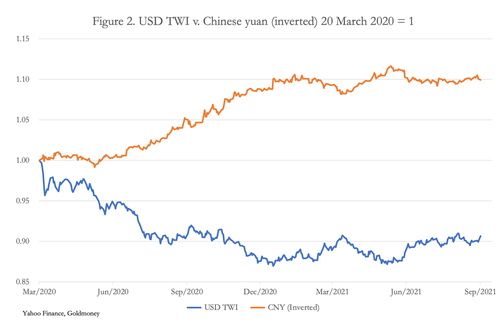

The fruits of China’s policies of restricting credit expansion are showing in the commodity prices she pays, which in her own currency have increased by ten per cent less than for dollar-based competition, judging by the exchange rate movements since the Fed reduced its funds rate to the zero bound and instigated monthly QE of $120bn on 19-23 March 2020 (see Figure 2). And while both currencies have moved broadly sideways since January, there is little doubt that the fundamentals point to an even stronger yuan and weaker dollar.

The domestic benefits of a relatively stronger yuan outweigh the margin compression suffered by China’s exporters. It is worth noting that as well as moderating credit demand, China is attempting to increase domestic consumer spending at the expense of the savings rate, so consumer demand will begin to matter more than exports to producers. It is in line with a long-term objective of China becoming less dependent on exports, and exporters will benefit from domestic sales growth instead. Furthermore, with China dominating global exports of intermediate and consumer goods and while western budget deficits are increasing and leading to yet greater trade deficits, Chinese exporters should be able to secure higher prices anyway.

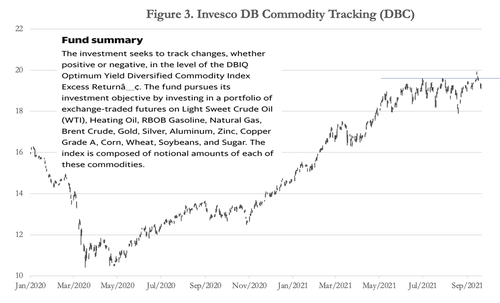

There can be little doubt that the budget deficits financed by monetary inflation in America, the EU, Japan and the UK, plus central bank stimulus packages are now undermining the purchasing power of all the major currencies. The consequences for their purchasing powers are now becoming apparent and attempts to calm markets and consumers by describing them as transient cuts little ice. In terms of their purchasing powers, these currencies are now in a race to the bottom.

Not only are the costs of production rising sharply, but following a brief pause of three months, commodity and energy prices look set to rise sharply. Figure 3 shows the Invesco commodity tracker, which having almost doubled since March 2020 now appears to be attempting a break out on the upside.

Since global competitiveness is no longer a priority, China would be sensible to let its yuan exchange rate rise against western currencies to help keep a lid on domestic prices and costs. It is, after all, a savings driven economy, with the sustainable characteristics of a strong currency relative to the dollar.

Conclusions

Having failed in their land-based military objectives, America’s undeclared tariff and financial wars against China are also coming to an end, to be replaced by a policy of maritime containment through the AUKUS partnership. Attempts to stem strategic losses in Asia have now ended with the withdrawal from Afghanistan and from other interventions.

The change in geopolitical policy is not yet widely appreciated. But the parlous state of US finances, dollar market bubbles, persistent and increasing price inflation and the inevitability of interest rate increases will make a policy backstop of maritime containment the only geostrategic option left to America.

By pursuing more cautious monetary policies, China is less exposed to the inevitable consequences of global monetary inflation. While yuan currency rates are managed instead of set by markets, it is now in China’s interest to see a stronger yuan to contain domestic price and cost inflation.

Even though fiat currencies could be destroyed by imploding asset bubbles, these factors contribute to a set of circumstances that appear to lead to a more peaceable outcome for the world than appeared likely before America and NATO withdrew from Afghanistan. There’s many a slip between cup and lip; but it was an outcome forecast by Halford Mackinder nearly eighty years ago.

Let us hope he was right.

https://ift.tt/3mhrLED

from ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/3mhrLED

via IFTTT

0 comments

Post a Comment