A Year Later, The Fact Fedwire Is Still There Tells Us Why Markets Have Done What They've Done

Authored by Jeffrey Snider via Alhambra Investments,

The world seemed to have everything going for it, for once, everything coming up favorable for the first time seemingly in forever. There were vaccines, financial government interventions worldwide just recklessly chucking money at anyone with a pulse, an end to the pandemic even normalcy right in front of us.

What could possibly have messed this up?

It was around 11:15 in the morning, Eastern Time, an otherwise totally nondescript Wednesday when something went wrong deep inside the computerized guts of the domestic interbank settlement system. No single thing, these settlement processing arrangements are interlocking sets of algorithmic-heavy progressions linking banks, financial markets of very kind, and trillions in volume every day for every possible money and financial purpose.

It was like someone just up and pulled the plug on something called Fedwire. The cascading failure eventually took down or restricted access to another 14 additional services, from FedCash and FedLine to Check 21, even a multiple of tied-in cryptocurrency exchanges such as CoinBase and Kraken were left scrambling by serious processing delays.

What happened?

To this day, no one has actually offered a complete explanation. Or much of one. Officials at the Federal Reserve, Fedwire’s operators, have only said it was some unspecified “operational error.”

The lone elaboration since it happened have been repeated assurances the event was not a cyberattack. As the Fed’s Treasury Market Practices Group noted about a month after it, they really want you to think there was nothing worth getting worked up over:

Staff noted that the root cause behind the disruption was identified quickly by staff and was not linked to a cybersecurity incident. Upon identifying the root cause, staff communicated updates with external market participants and extended daily deadlines while services were brought back online. Staff noted that this event underscored the importance of efficient and robust emergency communications procedures, and that they would continue building out communication tools to help bolster resiliency in the event of future disruptions.

Yes, resiliency. That does seem quite important.

An IMF review of this and other similar incidents around the world published in December 2021, with, I would imagine, the “latest” information available, again was notable for how little it offered:

No public information is available…According to a statement from the Federal Reserve, it took steps to help ensure the resilience of the Fedwire and NSS applications, including recovery to the point of failure. No further details were provided. Fedwire resumed normal operations after the 3 to 4 hours outage.

If not for what happened next, hardly anyone should care about any of this (admittedly, pretty much no one does still to this day). Unless it truly had been a cyberattack, and I sincerely doubt it was, this Fedwire thing easily left as some long-forgotten unimportant minutiae or footnote.

But…

The date of this event just so happened to be February 24, 2021 – a year ago today. Yet, for reasons that can’t be explained by dryly recounting the facts of that day, the dates February 24 and February 25 remain prominent on a whole range of financial market prices anyway 52 whole weeks later.

And it flies in the face of how the world seemed to be progressing from the 2020 COVID emergency. One day optimism was everywhere; the next, things really began to change in the wrong direction, a lot of things.

In other words, this isn’t now, nor has it been, really about Fedwire. Rather, the key word is another one beginning with the letter “f”, the exact opposite of resiliency.

Fragility.

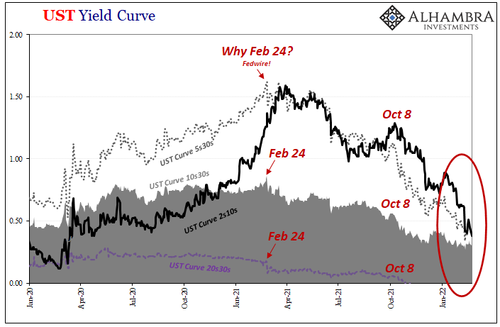

Start with the US Treasury yield curve itself, particularly its long end where, Irving Fisher, yields are an absolute combination of growth and inflation expectations. Up to February 24, 2021, the yield curve almost exclusively the long end had been steepening. Higher rates (and spreads between those rates) into the future are a wonderful sign of, well, the real potential to get back to normal by at least moving significantly in that direction.

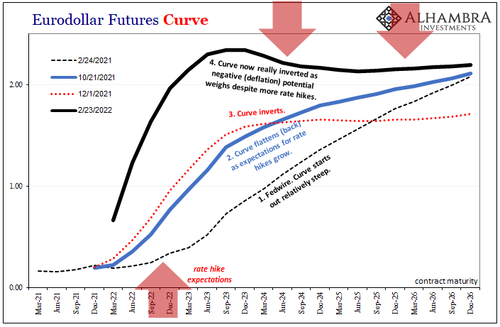

For the curve to suddenly stop steepening, and then move – for an entire year (tomorrow) – back the wrong way is a substantial and substantially unwelcome development. CPIs to the moon, tapering QE, double taper, now aggressive rate hikes, the world public convinced of a massive wave of inflation, yet for all this time in between flat, flatter, so flattened that just a few days ago parts of the curve nearly inverted (the 7s and 10s have touched on a few occasions now).

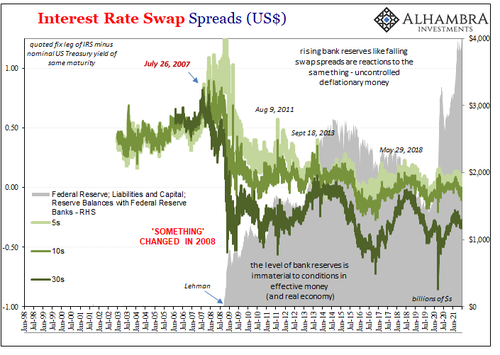

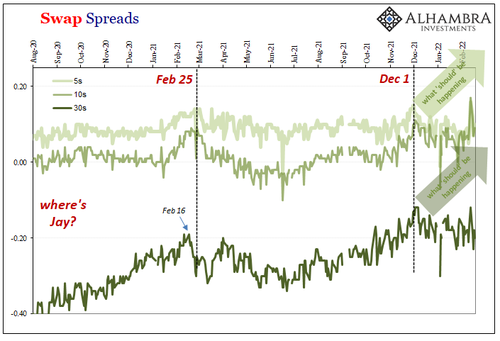

Not just the yield curve, also deep, key indications such as swap spreads. These, as noted a couple times recently, they really should be decompressing (rising) if that early 2021 optimism was gaining acceptance. The prospect for normalcy meaning normal thus higher rates (short and long), that would price right into decompressing spreads in this market more than anywhere else.

Both the flat curve like compressed swap spreads are clear indications of pessimism, the rising possibility the global system does not normalize; that more ends up going wrong than right, the potential for deflationary outcomes shifting to outweigh the inflationary or even reflationary trends hoping to the upside.

A three-hour delay in payment processing alone doesn’t explain these massive trend shifts.

What that delay triggered was a backlog in dealer settlements which seems to have spilled over (unofficially) into the next day’s processing – which included those same dealers who should have been fully bidding on a 7-year US Treasury auction.

While we don’t have the details, and no one seems to care about releasing them, the 7-year auction – and only that one auction – held on February 25 went badly awry. And, of course, the fact that it did was initially said to be inflation fears; as if banks were avoiding US Treasuries because inflation was by then already in danger of spiraling out of control.

With the added benefit of hindsight, and those market prices/indications subsequently proving this was never the case, a bad Treasury auction had been nothing more than a reminder of what can happen when dealers are distracted or missing to even a small degree.

The sequence of events at the time might have appeared innocuous enough in isolation: Fedwire shuts down for a couple hours on the 24th; money dealers have to play catch up but get clogged up by uncleared transactions while they do; by the afternoon of the 25th, a 7-year note auction goes noticeably awry as distracted dealers are noticeable by their absence; the entire global money system is reminded of actual “liquidity” when something like this happens, as it does all-too-frequently in the post-2007 world where bank reserves are useful only in the sense of setting a fairy tale narrative.

If not for pre-existing systemic fragility, none of this would’ve mattered. Instead, its aftermath was a reminder nothing had been fixed in this same post-2008 sense of monetary fragility. I wrote on March 25, 2021, exactly one month after the troublesome auction:

In other words, problems in the “plumbing” (and we still don’t specifically know what really happened that day last month) aren’t by themselves game-changers; they’ve only become more likely to blow up into major issues since August 2007 because no matter what any Fed Chairman says they never provide the world with anything monetary; the only flood is illusion and, in Jay’s case, self-selected self-delusion.

The probabilities of more things going wrong have long ago overwhelmed the probabilities of some things going or staying right. Perceptions of deflation (disinflation) overtook any leftover perceptions regarding last year’s “inflation.” A fragile global money system absolutely contributes to those former fears; a durably heightened risk of that potential for things going wrong.

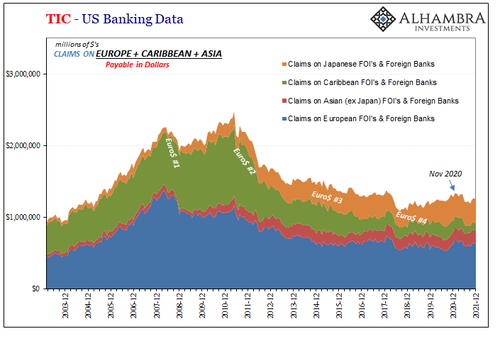

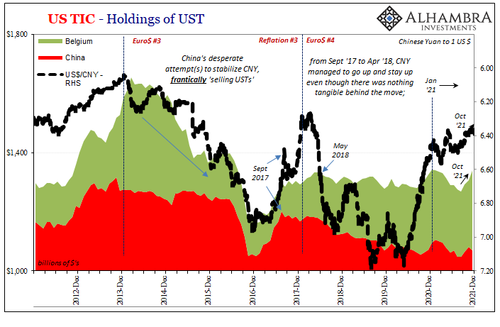

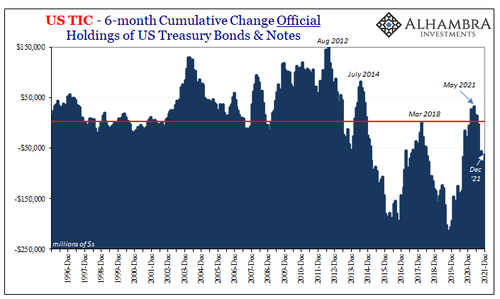

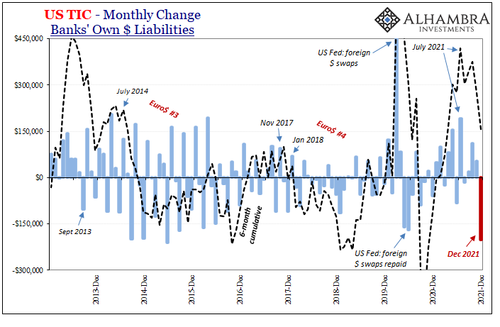

It hasn’t just been potential, though, has it? As we’ve meticulously and obsessive chronicled, real money prices and real economy results keep validating the fears, the natural outcomes of fragile. TIC, the dollar, lately eurodollar futures inversion which has exploded as we come up on Fedwire’s sordid little anniversary.

This isn’t to say that this was the only problem, or the only spark which set in motion this ongoing chain of rising deflationary potential. There were clear issues about China, TIC and Japan/Cayman Islands which cropped up back in December 2020. Early cracks in the reflationary dam.

Even swap spreads – take a look (above) at how the 30s had shifted more than a week before Fedwire and that bad 7s auction. It could’ve been a random fluctuation of spread compression, but given the perceptions about that time (inflation, interest rates nowhere to go but up) that sudden bout of downgrade really makes it seem like there were other problems in the monetary area which were becoming apparent just as February 24 and 25 approached.

If so, then the timing for this actually random event couldn’t have been worse. Though, thinking ahead, if not Fedwire a year ago then very likely something else.

That’s why markets are the way they are right now: the response to last year’s “inflation” had already been issued by the real money system itself – no need to get Jay Powell involved, even to explain what actually happened. After February 24, inflation never had a chance.

The public and the FOMC just never got the message though it’s been hiding in plain sight ever since that one Wednesday.

https://ift.tt/Jpgh2Nu

from ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/Jpgh2Nu

via IFTTT

0 comments

Post a Comment